News

Navigazione nell’ammissibilità del brevetto di invenzione Blockchain

INTRODUZIONE

La blockchain sta diventando centrale più che mai nei portafogli di brevetti FinTech, ma è più difficile ottenere protezione sulla blockchain rispetto alla maggior parte delle altre tecnologie. La decisione della Corte Suprema degli Stati Uniti nel caso Alice v. CLS Bank (2014) ha rafforzato i limiti su quali argomenti possono beneficiare della protezione brevettuale ai sensi dell’articolo 35. USC §101. Le odierne tecnologie basate su software non sempre superano il test in più parti di Alice per escludere le “idee astratte” dalla brevettabilità. Le imprese che sviluppano la tecnologia blockchain si trovano spesso a chiedersi se le loro invenzioni principali possano essere protette. Questo articolo spiega il nostro approccio per rispondere a queste domande.

La buona notizia è che le domande di brevetto blockchain ben redatte possono superare l’esame presso l’Ufficio brevetti e marchi degli Stati Uniti (USPTO). Negli ultimi dieci anni sono state depositate quasi 14.000 domande di brevetto basate su blockchain e sono stati rilasciati quasi 10.000 brevetti basati su blockchain.

Inizieremo con un “approfondimento” sul test Alice-Mayo delineato nella Revised Patent Object Matter Eligibility Guidance 2019 dell’USPTO, così come si applica alle rivendicazioni blockchain. Nella Sezione II analizziamo l’attuale panorama dei brevetti blockchain per identificare le tendenze nel deposito e nell’emissione dei brevetti blockchain. Infine, nella Sezione III forniamo alcuni suggerimenti pratici per la stesura di domande di brevetto che potrebbero garantire una forte protezione e aumentare il valore di un’impresa FinTech che sviluppa la tecnologia blockchain.

I. TEST ALICE-MAYO DI IDONEITÀ AL BREVETTO

Alice ha reso le idee astratte implementate su un computer generico non ammissibili ai brevetti e ha creato ostacoli all’ottenimento della protezione brevettuale su software come la blockchain. Sulla scia della decisione, l’USPTO ha pubblicato diversi documenti guida all’esame, tra cui la Guida all’ammissibilità dell’oggetto dei brevetti rivista del 2019 (“Guida”). La Guida ha fornito chiarimenti sull’ammissibilità dei brevetti per alcuni gruppi di idee astratte, come “concetti matematici”, “alcuni metodi di organizzazione dell’attività umana” e “processi mentali”. Questi sono esempi di categorie escluse dalla brevettabilità dai tribunali e sono note come “eccezioni giudiziarie” alla brevettabilità. La Guida delinea il test Alice-Mayo (basato sulla decisione della Corte Suprema nel caso Alice e il relativo Mayo Collaborative Services contro Prometheus Laboratories, Inc.) che includeva un’indagine su due fronti per determinare se un reclamo è “diretto a” un’eccezione giudiziaria .

Il primo passo del test Alice-Mayo (Step 1) dell’analisi di ammissibilità del brevetto è un’indagine per stabilire se la rivendicazione della domanda di brevetto è diretta a un processo, una macchina, una fabbricazione o una composizione della materia. Se la risposta è no, la richiesta è considerata non ammissibile al brevetto. Se la risposta è affermativa, allora il test procede alla seconda fase (Step 2) di ammissibilità del brevetto.

Il passaggio 2 comprende due passaggi secondari, il passaggio 2A e il passaggio 2B. La fase 2A consiste nell’investigare se la rivendicazione è diretta a una delle eccezioni giudiziarie non ammissibili ai brevetti – nel caso delle invenzioni software, una “idea astratta”. Se la rivendicazione non è diretta ad un’idea astratta, la rivendicazione si qualifica come oggetto ammissibile al brevetto. Tuttavia, il semplice fatto di essere “indirizzati verso” un’idea astratta non significa condannare l’idoneità. Invece, il passo 2B è un’indagine per stabilire se l’affermazione recita elementi aggiuntivi che equivalgono a “significativamente di più” rispetto all’idea astratta. In altre parole, la fase 2B è un’indagine per stabilire se la rivendicazione prevede un concetto inventivo aggiungendo limitazioni oltre un’idea astratta non ben compresa, di routine, convenzionale. Se la rivendicazione recita elementi aggiuntivi che ammontano a molto di più dell’idea astratta, allora la rivendicazione si qualifica come brevettabile.

Il principale chiarimento fornito dalla Guida è quello di stabilire a analisi su due fronti al punto 2A. Il polo 1 chiede se l’affermazione recita una “idea astratta”. Il polo 2 è una domanda se l’affermazione recita elementi aggiuntivi che integrano l’idea astratta in un’applicazione pratica. La logica alla base del polo 2 è determinare se l’affermazione si applica, si basa o utilizza l’idea astratta in un modo che impone una limitazione significativa sull’idea astratta, in modo tale che l’affermazione sia più di uno sforzo redazionale progettato per monopolizzare l’idea astratta . Va notato che secondo il test di Alice-Mayo, “recitare” un’idea astratta è diverso dall’essere “indirizzati verso” un’idea astratta. Un’affermazione che recita un’idea astratta include semplicemente un’idea astratta. Ma per essere “diretta verso” un’idea astratta, l’affermazione deve fallire sia sul polo 1 che sul polo 2 del passo 2A.

Determinare se l’affermazione recita elementi aggiuntivi che integrano l’idea astratta in un’applicazione pratica sotto il polo 2 implica (a) identificare se l’affermazione include elementi aggiuntivi che recitano elementi oltre l’idea astratta e (b) valutare gli elementi aggiuntivi sia individualmente che collettivamente per determinare se integrano l’eccezione in un’applicazione pratica o utilizzano l’idea astratta in un modo che impone un limite significativo all’idea astratta, in modo tale che l’affermazione sia più di uno sforzo redazionale progettato per monopolizzare l’idea astratta.

II. ANALISI DEL PAESAGGIO DEI BREVETTI BLOCKCHAIN

Tra gennaio 2013 e ottobre 2023 sono state depositate e pubblicate 13.854 domande di brevetto sulla tecnologia blockchain presso l’USPTO. Durante questo periodo sono stati concessi 9.442 brevetti blockchain.

Figura 1: Grafico delle domande di brevetto blockchain depositate presso l’USPTO e dei brevetti blockchain concessi dall’USPTO.

Nel periodo tra il 2015 e il 2019, si è registrato un aumento sia del numero di domande di brevetto blockchain depositate, sia del numero di brevetti blockchain rilasciati. Il primo periodo è stato seguito da un secondo periodo tra il 2019 e il 2022 in cui il numero di domande depositate si è stabilizzato mentre il numero di brevetti rilasciati è diminuito. Circa 1.160 domande depositate sono state abbandonate durante il secondo periodo e 560 delle 1.160 domande abbandonate sono state respinte sulla base del §101 da parte dell’USPTO (come mostrato nella FIG. 2).

Figura 2: Grafico delle domande di brevetto blockchain abbandonate in funzione dell’anno e grafico delle domande abbandonate che hanno dovuto affrontare un rigetto ai sensi del § 101.

In termini di richiedenti brevetti, Advanced New Technologies ha ottenuto il maggior numero di brevetti blockchain negli Stati Uniti (1311 brevetti), seguita da IBM (790 brevetti), Bank of America (198 brevetti), Ant Group Co. Ltd.[1]/ (188 brevetti), Mastercard Inc. (137 brevetti) e One Trust LLC (123 brevetti).

Figura 3: Grafico dei brevetti blockchain rilasciati ai richiedenti negli Stati Uniti

I tre principali detentori di brevetti blockchain statunitensi sono Advanced New Technologies, IBM e Bank of America. Per le domande di brevetto depositate tra il 2016 e il 2019, IBM ha ottenuto il maggior numero di brevetti blockchain. Il numero di brevetti blockchain rilasciati per nuove tecnologie avanzate basati su domande depositate dal 2017 ha superato quello di IBM.

Figura 4: Brevetti rilasciati ai primi 3 richiedenti in funzione dell’anno di deposito.

Le domande di brevetto Blockchain depositate dal 2021 sono probabilmente ancora in fase di perseguimento davanti all’USPTO, e quindi molte di queste domande non sono ancora state rilasciate.

III. CONSIGLI PRATICI PER PROSEGUIRE LE APPLICAZIONI BLOCKCHAIN

Sebbene il test Alice-Mayo abbia inizialmente reso non brevettabili molte invenzioni legate al software, negli ultimi anni le prospettive per la brevettabilità delle domande di brevetto blockchain sono migliorate. Nell’ultimo decennio sono stati rilasciati quasi 10.000 brevetti legati alla blockchain. Tuttavia, consigliamo ai richiedenti che cercano protezione per la loro tecnologia blockchain di redigere le rivendicazioni e le specifiche delle loro domande di brevetto tenendo presente il test Alice-Mayo.

Suggerimento 1: risolvi 101 problemi con l’Examiner.

Il primo aspetto fondamentale dei nostri risultati è che i richiedenti farebbero meglio a risolvere un rifiuto Alice/§101 con l’esaminatore di brevetti piuttosto che appellarsi al Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). Abbiamo identificato un totale di 38 domande di brevetto relative alla blockchain in cui un richiedente ha presentato ricorso contro il rifiuto §101 di un esaminatore. La perquisizione ha dato esito a 38 ricorsi. Solo in quattro dei 38 ricorsi, il PTAB ha annullato il rifiuto del §101 dell’esaminatore: in altre parole, il PTAB ha confermato il rifiuto del §101 dell’esaminatore circa il 90% delle volte. In tre dei quattro annullamenti, il PTAB ha emesso nuove motivazioni per il rigetto del §101. Di conseguenza, solo uno dei 38 ricorsi è riuscito a superare il rigetto del §101 presso il PTAB, con un tasso di fallimento del 97,3%. Notiamo che dei 37 ricorsi che non sono riusciti a superare il rigetto del §101, 5 domande sono state successivamente accolte sulla base di modifiche della domanda davanti all’esaminatore. È chiaro che una strategia di collaborazione con l’esaminatore per risolvere un rifiuto Alice/§101 in una domanda di brevetto blockchain ha molte più probabilità di portare al rilascio di un brevetto.

Suggerimento 2: non ammettere che un’affermazione blockchain sia “diretta a” un’idea astratta.

Il secondo aspetto fondamentale è che le domande dovrebbero essere redatte tenendo d’occhio il polo 2 del passaggio 2A perché è altamente improbabile che le affermazioni blockchain siano considerate brevettabili ai sensi del polo 1 del passaggio 2A (vale a dire, trovate a non “recitare” un’idea astratta) . Dei 38 ricorsi che abbiamo analizzato, si è riscontrato che in ogni caso l’affermazione recitava un’idea astratta (ad esempio, metodi di organizzazione dell’attività umana come attività commerciali che possono essere eseguite nella mente). Nell’ambito dell’analisi del polo 2, il PTAB in genere pone due domande separate: 1) L’affermazione include elementi aggiuntivi oltre all’idea astratta? 2) Gli elementi aggiuntivi integrano l’idea astratta con un’applicazione pratica? Se il PTAB ritiene che non vi siano elementi aggiuntivi oltre all’idea astratta, la richiesta verrà generalmente considerata non ammissibile ai sensi del test Alice-Mayo.

Per garantire che la rivendicazione contenga elementi aggiuntivi con il significato del polo 2 della fase 2A, si consiglia vivamente ai richiedenti il brevetto di includere dettagli sostanziali sulle operazioni tecniche della loro invenzione nelle rivendicazioni. Sebbene ciò possa rendere le affermazioni più lunghe e potenzialmente di portata più ristretta, probabilmente aumenterà le possibilità di superare la prima domanda nell’analisi del polo 2. Questo parere è supportato dai cinque ricorsi (dei 38 ricorsi sopra menzionati) in cui il PTAB ha confermato il rigetto di un esaminatore in 101 casi, ma le domande corrispondenti sono state successivamente emesse sulla base delle modifiche della richiesta apportate dal richiedente. In questi cinque casi, la lunghezza media delle rivendicazioni ritenute non idonee al brevetto da parte di PTAB era di 150 parole, mentre la lunghezza media delle rivendicazioni alla fine accettate era di 319 parole.[2]/

Suggerimento 3: integra i concetti della blockchain in un’applicazione pratica.

Infine, i candidati dovrebbero garantire che gli elementi tecnici aggiuntivi integrino l’idea astratta in un’applicazione pratica. Il PTAB ha ritenuto che i miglioramenti nella tecnologia piuttosto che i miglioramenti nell’idea astratta costituiscano l’integrazione di un’idea astratta in un’applicazione pratica. Ad esempio, PTAB ha ritenuto che una nuova idea astratta implementata su un computer generico sia ancora un’idea astratta.[3] I richiedenti dovrebbero prendere in considerazione l’implementazione nelle loro affermazioni di funzionalità che non possono essere realizzate dalla mente umana anche se ipoteticamente gli viene concesso un notevole periodo di tempo.[4] Nelle affermazioni blockchain, ciò può includere l’aggiunta di limitazioni relative a concetti tecnici come l’hashing o la verifica della firma digitale che sono impossibili da realizzare per una mente umana.

CONCLUSIONE

I dati mostrano che le invenzioni blockchain costituiscono una parte considerevole dei portafogli di brevetti tecnologici e una domanda di brevetto relativa alla tecnologia blockchain può essere posizionata per avere successo presso l’ufficio brevetti seguendo il nostro approccio descritto sopra. Noi di Mintz siamo pronti ad assistere la tua azienda nella valutazione della migliore strategia IP per le tue invenzioni blockchain.

Coautore di Siddharth Bhardwaj, Summer Associate 2024.

[1]/ Ant Group Co. Ltd è un’affiliata di Advanced New Technologies.

[2]/ In un prossimo articolo discuteremo dei ricorsi al PTAB: uno in cui il PTAB ha annullato il rifiuto §101 di un esaminatore di brevetti e l’altro in cui il PTAB ha confermato il rifiuto §101 di un esaminatore di brevetti ma le rivendicazioni respinte sono state successivamente accolte dopo la modifica della rivendicazione.

[3] Vedi pag. 11, Decisione di ricorso del 4 novembre 2021 del ricorso ‘0030 (citando Synopsys, Inc. contro Mentor Graphics Corp., 839 F.3d 1138, 1151 (Fed. Cir. 2016))

[4] Vedi pag. 18, Decisione di ricorso del 19 agosto 2020, della domanda statunitense n. 14/719,030.

News

An enhanced consensus algorithm for blockchain

The introduction of the link and reputation evaluation concepts aims to improve the stability and security of the consensus mechanism, decrease the likelihood of malicious nodes joining the consensus, and increase the reliability of the selected consensus nodes.

The link model structure based on joint action

Through the LINK between nodes, all the LINK nodes engage in consistent activities during the operation of the consensus mechanism. The reputation evaluation mechanism evaluates the trustworthiness of nodes based on their historical activity status throughout the entire blockchain. The essence of LINK is to drive inactive nodes to participate in system activities through active nodes. During the stage of selecting leader nodes, nodes are selected through self-recommendation, and the reputation evaluation of candidate nodes and their LINK nodes must be qualified. The top 5 nodes of the total nodes are elected as leader nodes through voting, and the nodes in their LINK status are candidate nodes. In the event that the leader node goes down, the responsibility of the leader node is transferred to the nodes in its LINK through the view-change. The LINK connection algorithm used in this study is shown in Table 2, where LINKm is the linked group and LINKP is the percentage of linked nodes.

Table 2 LINK connection algorithm.

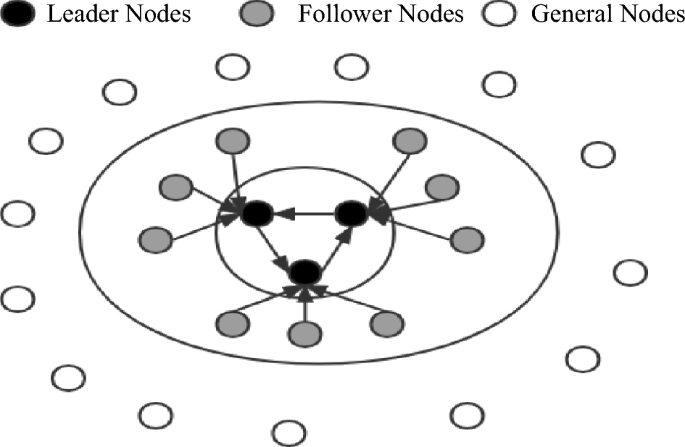

Node type

This paper presents a classification of nodes in a blockchain system based on their functionalities. The nodes are divided into three categories: leader nodes (LNs), follower nodes (FNs), and general nodes (Ns). The leader nodes (LNs) are responsible for producing blocks and are elected through voting by general nodes. The follower nodes (FNs) are nodes that are linked to leader nodes (LNs) through the LINK mechanism and are responsible for validating blocks. General nodes (N) have the ability to broadcast and disseminate information, participate in elections, and vote. The primary purpose of the LINK mechanism is to act in combination. When nodes are in the LINK, there is a distinction between the master and slave nodes, and there is a limit to the number of nodes in the LINK group (NP = {n1, nf1, nf2 ……,nfn}). As the largest proportion of nodes in the system, general nodes (N) have the right to vote and be elected. In contrast, leader nodes (LNs) and follower nodes (FNs) do not possess this right. This rule reduces the likelihood of a single node dominating the block. When the system needs to change its fundamental settings due to an increase in the number of nodes or transaction volume, a specific number of current leader nodes and candidate nodes need to vote for a reset. Subsequently, general nodes need to vote to confirm this. When both confirmations are successful, the new basic settings are used in the next cycle of the system process. This dual confirmation setting ensures the fairness of the blockchain to a considerable extent. It also ensures that the majority holds the ultimate decision-making power, thereby avoiding the phenomenon of a small number of nodes completely controlling the system.

After the completion of a governance cycle, the blockchain network will conduct a fresh election for the leader and follower nodes. As only general nodes possess the privilege to participate in the election process, the previous consortium of leader and follower nodes will lose their authorization. In the current cycle, they will solely retain broadcasting and receiving permissions for block information, while their corresponding incentives will also decrease. A diagram illustrating the node status can be found in Fig. 1.

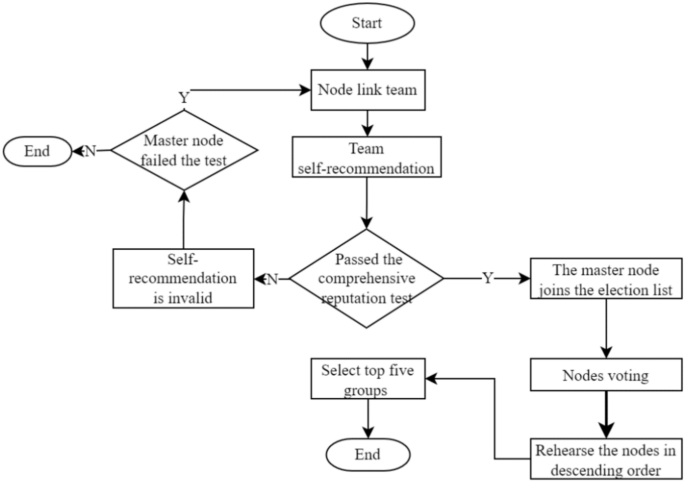

Election method

The election method adopts the node self-nomination mode. If a node wants to participate in an election, it must form a node group with one master and three slaves. One master node group and three slave node groups are inferred based on experience in this paper; these groups can balance efficiency and security and are suitable for other project collaborations. The successfully elected node joins the leader node set, and its slave nodes enter the follower node set. Considering the network situation, the maximum threshold for producing a block is set to 1 s. If the block fails to be successfully generated within the specified time, it is regarded as a disconnected state, and its reputation score is deducted. The node is skipped, and in severe cases, a view transformation is performed, switching from the master node to the slave node and inheriting its leader’s rights in the next round of block generation. Although the nodes that become leaders are high-reputation nodes, they still have the possibility of misconduct. If a node engages in misconduct, its activity will be immediately stopped, its comprehensive reputation score will be lowered, it will be disqualified from participating in the next election, and its equity will be reduced by 30%. The election process is shown in Fig. 2.

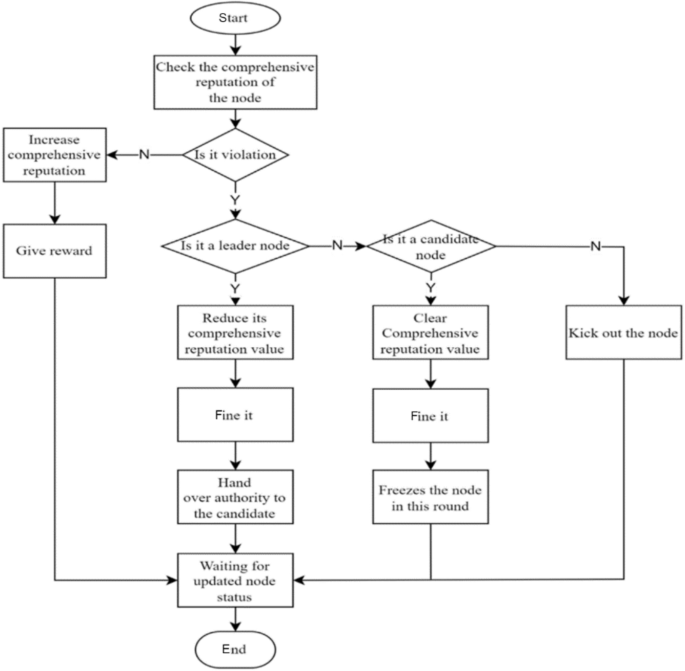

Incentives and penalties

To balance the rewards between leader nodes and ordinary nodes and prevent a large income gap, two incentive/penalty methods will be employed. First, as the number of network nodes and transaction volume increase, more active nodes with significant stakes emerge. After a prolonged period of running the blockchain, there will inevitably be significant class distinctions, and ordinary nodes will not be able to win in the election without special circumstances. To address this issue, this paper proposes that rewards be reduced for nodes with stakes exceeding a certain threshold, with the reduction rate increasing linearly until it reaches zero. Second, in the event that a leader or follower node violates the consensus process, such as by producing a block out of order or being unresponsive for an extended period, penalties will be imposed. The violation handling process is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Violation handling process.

Comprehensive reputation evaluation and election mechanism based on historical transactions

This paper reveals that the core of the DPoS consensus mechanism is the election process. If a blockchain is to run stably for a long time, it is essential to consider a reasonable election method. This paper proposes a comprehensive reputation evaluation election mechanism based on historical records. The mechanism considers the performance indicators of nodes in three dimensions: production rate, tokens, and validity. Additionally, their historical records are considered, particularly whether or not the nodes have engaged in malicious behavior. For example, nodes that have ever been malicious will receive low scores during the election process unless their overall quality is exceptionally high and they have considerable support from other nodes. Only in this case can such a node be eligible for election or become a leader node. The comprehensive reputation score is the node’s self-evaluation score, and the committee size does not affect the computational complexity.

Moreover, the comprehensive reputation evaluation proposed in this paper not only is a threshold required for node election but also converts the evaluation into corresponding votes based on the number of voters. Therefore, the election is related not only to the benefits obtained by the node but also to its comprehensive evaluation and the number of voters. If two nodes receive the same vote, the node with a higher comprehensive reputation is given priority in the ranking. For example, in an election where node A and node B each receive 1000 votes, node A’s number of stake votes is 800, its comprehensive reputation score is 50, and only four nodes vote for it. Node B’s number of stake votes is 600, its comprehensive reputation score is 80, and it receives votes from five nodes. In this situation, if only one leader node position remains, B will be selected as the leader node. Displayed in descending order of priority as comprehensive credit rating, number of voters, and stake votes, this approach aims to solve the problem of node misconduct at its root by democratizing the process and subjecting leader nodes to constraints, thereby safeguarding the fundamental interests of the vast majority of nodes.

Comprehensive reputation evaluation

This paper argues that the election process of the DPoS consensus mechanism is too simplistic, as it considers only the number of election votes that a node receives. This approach fails to comprehensively reflect the node’s actual capabilities and does not consider the voters’ election preferences. As a result, nodes with a significant stake often win and become leader nodes. To address this issue, the comprehensive reputation evaluation score is normalized considering various attributes of the nodes. The scoring results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Comprehensive reputation evaluation.

Since some of the evaluation indicators in Table 3 are continuous while others are discrete, different normalization methods need to be employed to obtain corresponding scores for different indicators. The continuous indicators include the number of transactions/people, wealth balance, network latency, network jitter, and network bandwidth, while the discrete indicators include the number of violations, the number of successful elections, and the number of votes. The value range of the indicator “number of transactions/people” is (0,1), and the value range of the other indicators is (0, + ∞). The equation for calculating the “number of transactions/people” is set as shown in Eq. (1).

$$A_{1} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {0,} \hfill & {{\text{G}} = 0} \hfill \\ {\frac{{\text{N}}}{{\text{G}}}*10,} \hfill & {{\text{G}} > 0} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$

(1)

where N represents the number of transactional nodes and G represents the number of transactions. It reflects the degree of connection between the node and other nodes. Generally, nodes that transact with many others are safer than those with a large number of transactions with only a few nodes. The limit value of each item, denoted by x, is determined based on the situation and falls within the specified range, as shown in Eq. (2). The wealth balance and network bandwidth indicators use the same function to set their respective values.

$${A}_{i}=20*\left(\frac{1}{1+{e}^{-{a}_{i}x}}-0.5\right)$$

(2)

where x indicates the value of this item and expresses the limit value.

In Eq. (3), x represents the limited value of this indicator. The lower the network latency and network jitter are, the higher the score will be.

The last indicators, which are the number of violations, the number of elections, and the number of votes, are discrete values and are assigned different scores according to their respective ranges. The scores corresponding to each count are shown in Table 4.

$$A_{3} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {10*\cos \frac{\pi }{200}x,} \hfill & {0 \le x \le 100} \hfill \\ {0,} \hfill & {x > 100} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$

(3)

Table 4 Score conversion.

The reputation evaluation mechanism proposed in this paper comprehensively considers three aspects of nodes, wealth level, node performance, and stability, to calculate their scores. Moreover, the scores obtain the present data based on historical records. Each node is set as an M × N dimensional matrix, where M represents M times the reputation evaluation score and N represents N dimensions of reputation evaluation (M < = N), as shown in Eq. (4).

$${\text{N}} = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {a_{11} } & \cdots & {a_{1n} } \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {a_{m1} } & \cdots & {a_{mn} } \\ \end{array} } \right)$$

(4)

The comprehensive reputation rating is a combined concept related to three dimensions. The rating is set after rating each aspect of the node. The weight w and the matrix l are not fixed. They are also transformed into matrix states as the position of the node in the system changes. The result of the rating is set as the output using Eq. (5).

$$\text{T}=\text{lN}{w}^{T}=\left({l}_{1}\dots {\text{l}}_{\text{m}}\right)\left(\begin{array}{ccc}{a}_{11}& \cdots & {a}_{1n}\\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {a}_{m1}& \cdots & {a}_{mn}\end{array}\right){\left({w}_{1}\dots {w}_{n}\right)}^{T}$$

(5)

Here, T represents the comprehensive reputation score, and l and w represent the correlation coefficient. Because l is a matrix of order 1*M, M is the number of times in historical records, and M < = N is set, the number of dimensions of l is uncertain. Set the term l above to add up to 1, which is l1 + l2 + …… + ln = 1; w is also a one-dimensional matrix whose dimension is N*1, and its purpose is to act as a weight; within a certain period of time, w is a fixed matrix, and w will not change until the system changes the basic settings.

Assume that a node conducts its first comprehensive reputation rating, with no previous transaction volume, violations, elections or vote. The initial wealth of the node is 10, the latency is 50 ms, the jitter is 100 ms, and the network bandwidth is 100 M. According to the equation, the node’s comprehensive reputation rating is 41.55. This score is relatively good at the beginning and gradually increases as the patient participates in system activities continuously.

Voting calculation method

To ensure the security and stability of the blockchain system, this paper combines the comprehensive reputation score with voting and randomly sorts the blocks, as shown in Eqs. (3–6).

$$Z=\sum_{i=1}^{n}{X}_{i}+nT$$

(6)

where Z represents the final election score, Xi represents the voting rights earned by the node, n is the number of nodes that vote for this node, and T is the comprehensive reputation score.

The voting process is divided into stake votes and reputation votes. The more reputation scores and voters there are, the more total votes that are obtained. In the early stages of blockchain operation, nodes have relatively few stakes, so the impact of reputation votes is greater than that of equity votes. This is aimed at selecting the most suitable node as the leader node in the early stage. As an operation progresses, the role of equity votes becomes increasingly important, and corresponding mechanisms need to be established to regulate it. The election vote algorithm used in this paper is shown in Table 5.

Table 5 Election vote counting algorithm.

This paper argues that the election process utilized by the original DPoS consensus mechanism is overly simplistic, as it relies solely on the vote count to select the node that will oversee the entire blockchain. This approach cannot ensure the security and stability of the voting process, and if a malicious node behaves improperly during an election, it can pose a significant threat to the stability and security of the system as well as the safety of other nodes’ assets. Therefore, this paper proposes a different approach to the election process of the DPoS consensus mechanism by increasing the complexity of the process. We set up a threshold and optimized the vote-counting process to enhance the security and stability of the election. The specific performance of the proposed method was verified through experiments.

The election cycle in this paper can be customized, but it requires the agreement of the blockchain committee and general nodes. The election cycle includes four steps: node self-recommendation, calculating the comprehensive reputation score, voting, and replacing the new leader. Election is conducted only among general nodes without affecting the production or verification processes of leader nodes or follower nodes. Nodes start voting for preferred nodes. If they have no preference, they can use the LINK mechanism to collaborate with other nodes and gain additional rewards.

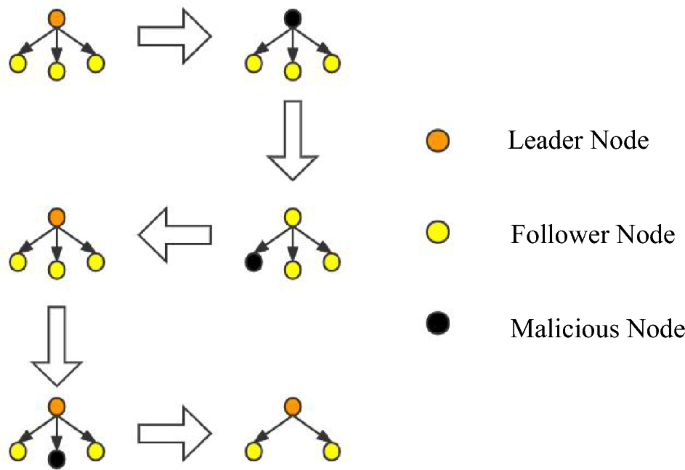

View changes

During the consensus process, conducting a large number of updates is not in line with the system’s interests, as the leader node (LN) and follower node (FN) on each node have already been established. Therefore, it is crucial to handle problematic nodes accurately when issues arise with either the LN or FN. For instance, when a node fails to perform its duties for an extended period or frequently fails to produce or verify blocks within the specified time range due to latency, the system will precisely handle them. For leader nodes, if they engage in malicious behavior such as producing blocks out of order, the behavior is recorded, and their identity as a leader node is downgraded to a follower node. The follower node inherits the leader node’s position, and the nature of their work is transformed as they swap their responsibilities of producing and verifying blocks with their original work. This type of behavior will not significantly affect the operation of the blockchain system. Instead of waiting until the end of the current committee round to punish malicious nodes, dynamic punishment is imposed on the nodes that affect the operation of the blockchain system to maintain system security. The view change operation is illustrated in Fig. 4.

In traditional PBFT, view changes are performed according to the view change protocol by changing the view number V to the next view number V + 1. During this process, nodes only receive view change messages and no other messages from other nodes. In this paper, the leader node group (LN) and follower node group (FN) are selected through an election of the LINK group. The node with LINKi[0] is added to the LN leader node group, while the other three LINK groups’ follower nodes join the FN follower node group since it is a configuration pattern of one master and three slaves. The view change in this paper requires only rearranging the node order within the LINK group to easily remove malicious nodes. Afterward, the change is broadcast to other committee nodes, and during the view transition, the LINK group does not receive block production or verification commands from the committee for stability reasons until the transition is completed.

News

The Hype Around Blockchain Mortgage Has Died Down, But This CEO Still Believes

LiquidFi Founder Ian Ferreira Sees Huge Potential in Blockchain Despite Hype around technology is dead.

“Blockchain technology has been a buzzword for a long time, and it shouldn’t be,” Ferriera said. “It should be a technology that lives in the background, but it makes everything much more efficient, much more transparent, and ultimately it saves costs for everyone. That’s the goal.”

Before founding his firm, Ferriera was a portfolio manager at a hedge fund, a job that ended up revealing “interesting intricacies” related to the mortgage industry.

Being a mortgage trader opened Ferriera’s eyes to a lot of the operational and infrastructure problems that needed to be solved in the mortgage-backed securities industry, he said. That later led to the birth of LiquidFi.

“The point of what we do is to get raw data attached to a resource [a loan] on a blockchain so that it’s provable. You reduce that trust problem because you have the data, you have the document associated with that data,” said the LiquidFi CEO.

Ferriera spoke with National Mortgage News about the value of blockchain technology, why blockchain hype has fizzled out, and why it shouldn’t.

News

New bill pushes Department of Veterans Affairs to examine how blockchain can improve its work

The Department of Veterans Affairs would have to evaluate how blockchain technology could be used to improve benefits and services offered to veterans, according to a legislative proposal introduced Tuesday.

The bill, sponsored by Rep. Nancy Mace, R-S.C., would direct the VA to “conduct a comprehensive study of the feasibility, potential benefits, and risks associated with using distributed ledger technology in various programs and services.”

Distributed ledger technology, including blockchain, is used to protect and track information by storing data across multiple computers and keeping a record of its use.

According to the text of the legislation, which Mace’s office shared exclusively with Nextgov/FCW ahead of its publication, blockchain “could significantly improve benefits allocation, insurance program management, and recordkeeping within the Department of Veterans Affairs.”

“We need to bring the federal government into the 21st century,” Mace said in a statement. “This bill will open the door to research on improving outdated systems that fail our veterans because we owe it to them to use every tool at our disposal to improve their lives.”

Within one year of the law taking effect, the Department of Veterans Affairs will be required to submit a report to the House and Senate Veterans Affairs committees detailing its findings, as well as the benefits and risks identified in using the technology.

The mandatory review is expected to include information on how the department’s use of blockchain could improve the way benefits decisions are administered, improve the management and security of veterans’ personal data, streamline the insurance claims process, and “increase transparency and accountability in service delivery.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs has been studying the potential benefits of using distributed ledger technology, with the department emission a request for information in November 2021 seeking input from contractors on how blockchain could be leveraged, in part, to streamline its supply chains and “secure data sharing between institutions.”

The VA’s National Institute of Artificial Intelligence has also valued the use of blockchain, with three of the use cases tested during the 2021 AI tech sprint focused on examining its capabilities.

Mace previously introduced a May bill that would direct Customs and Border Protection to create a public blockchain platform to store and share data collected at U.S. borders.

Lawmakers also proposed additional measures that would push the Department of Veterans Affairs to consider adopting other modernized technologies to improve veteran services.

Rep. David Valadao, R-Calif., introduced legislation in June that would have directed the department to report to lawmakers on how it plans to expand the use of “certain automation tools” to process veterans’ claims. The House of Representatives Subcommittee on Disability Assistance and Memorial Affairs gave a favorable hearing on the congressman’s bill during a Markup of July 23.

News

California DMV Uses Blockchain to Fight Auto Title Fraud

TDR’s Three Takeaways: California DMV Uses Blockchain to Fight Fraud

- California DMV uses blockchain technology to manage 42 million auto titles.

- The initiative aims to improve safety and reduce car title fraud.

- The immutable nature of blockchain ensures accurate and tamper-proof records.

The California Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) is implementing blockchain technology to manage and secure 42 million auto titles. This innovative move aims to address and reduce the persistent problem of auto title fraud, a problem that costs consumers and the industry millions of dollars each year. By moving to a blockchain-based system, the DMV is taking advantage of the technology’s key feature: immutability.

Blockchain, a decentralized ledger technology, ensures that once a car title is registered, it cannot be altered or tampered with. This creates a highly secure and transparent system, significantly reducing the risk of fraudulent activity. Every transaction and update made to a car title is permanently recorded on the blockchain, providing a complete and immutable history of the vehicle’s ownership and status.

As first reported by Reuters, the DMV’s adoption of blockchain isn’t just about preventing fraud. It’s also aimed at streamlining the auto title process, making it more efficient and intuitive. Traditional auto title processing involves a lot of paperwork and manual verification, which can be time-consuming and prone to human error. Blockchain technology automates and digitizes this process, reducing the need for physical documents and minimizing the chances of errors.

Additionally, blockchain enables faster verification and transfer of car titles. For example, when a car is sold, the transfer of ownership can be done almost instantly on the blockchain, compared to days or even weeks in the conventional system. This speed and efficiency can benefit both the DMV and the vehicle owners.

The California DMV’s move is part of a broader trend of government agencies exploring blockchain technology to improve their services. By adopting this technology, the DMV is setting a precedent for other states and industries to follow, showcasing blockchain’s potential to improve safety and efficiency in public services.

-

Ethereum12 months ago

Ethereum12 months agoEthereum Posts First Consecutive Monthly Losses Since August 2023 on New ETFs

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoCryptocurrency Regulation in Slovenia 2024

-

News12 months ago

News12 months agoNew bill pushes Department of Veterans Affairs to examine how blockchain can improve its work

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoThink You Own Your Crypto? New UK Law Would Ensure It – DL News

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoUpbit, Coinone, Bithumb Face New Fees Under South Korea’s Cryptocurrency Law

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoA Blank Slate for Cryptocurrencies: Kamala Harris’ Regulatory Opportunity

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoBahamas Passes Cryptocurrency Bill Designed to Prevent FTX, Terra Disasters

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoIndia to Follow G20 Policy for Cryptocurrency Regulation: MoS Finance

-

News1 year ago

News1 year ago“Captain Tsubasa – RIVALS” launches on Oasys Blockchain

-

Ethereum1 year ago

Ethereum1 year agoComment deux frères auraient dérobé 25 millions de dollars lors d’un braquage d’Ethereum de 12 secondes • The Register

-

News12 months ago

News12 months agoEU supports 15 startups to fight online disinformation with blockchain

-

News1 year ago

News1 year agoSolana ranks the fastest blockchain in the world, surpassing Ethereum, Polygon ⋆ ZyCrypto