News

What Happened to Toni Lane Casserly, the “Joan of Arc of Blockchain” Who Died in Her Childhood Home?

She sits in an off-white easy chair in a nondescript room. She’s relaxed yet radiant, her dark eyes dancing with anticipation. Across from her, an interviewer, a seemingly affable dude in a graphic tee, grins and points. That’s her cue. She flutters her fingers outward from her face. Her painted lips part. “I’ll beeeee seeing youuuuu / In all the old familiar places.…” Toni Lane Casserly, channeling Billie Holiday, sings the classic song a cappella with just about perfect pitch. The dude swoons.

You wouldn’t know it from the cold open, but this is a conversation about the blockchain technology that fuels cryptocurrencies. About the new world order Toni is working to construct, an inverted model of society as we know it.

The date is December 7, 2018. Toni is 27 and industry-famous, at the top of her game. As one of the few women in crypto, she stands out, not just because of her gender but because of her style—free-flowing, jazzy—and her values. While many of her peers hole up in hacker houses and race to pump out “magic internet money,” as one bluntly puts it, Toni worries over issues like state violence, mass dispossession, disaster-fueled climate migration, and the gatekeeping of wealth by the ruling class. Let us not turn away, she counsels. Together we can fix this. We must.

Part of the solution, she believes, are blockchains—permanent digital ledgers maintained by decentralized networks of computers. These data banks store documents and financial transactions; they keep score. And ultimately, Toni preaches, they will introduce a new kind of accountability, put control in the hands of the people, and shift the paradigms of global power.

Her passion is compelling, seductive even, and hits with a sense of authority. She’s been in the blockchain field for half a decade, ever since she bailed on a communications program at the University of Texas, leaving behind her family and theater-kid roots for the burgeoning crypto scene of the Bay Area. Her first job, at a bitcoin tipping company later acquired by Airbnb, was just the start. A genius networker, she soon parlayed her prolific people skills into more impressive roles. In 2015, she was named CEO of Cointelegraph, a publication that chronicled crypto news and intrigue and connected her with its biggest players. She then homed in on consulting, making a name for herself as a marketing whisperer for companies like the stablecoin Tether.

Toni’s big dream, though, is to launch a blockchain start-up of her own. She’s written a pitch deck for one called Cultu.re, which would issue and track personal identity and ownership documents, like blockchain marriage certificates and property deeds. Users would no longer be reliant on corrupt governments or financial institutions for these things. Even more exciting, her ecosystem would assign each of its members a peer-to-peer social credit score of sorts—a trustworthiness metric that would band people together and “leverage good behavior to redistribute resources.” In fiery talks at events, from the Japan Blockchain Conference in Tokyo to the Crypto Symposium in Mykonos, Toni positions Cultu.re as a means to “destroy the state.” Via YouTube, her presentations reach tens of thousands around the world. Industry media hail her as a young star. She earns a nickname: the Joan of Arc of Blockchain.

Toni is relentless in her mission—until one day, she isn’t. Not even a year from now, she will suddenly drop off the map, both metaphorically and literally. Her social media accounts will sit silent. Friends won’t hear from or about her for six months, until the spring of 2020, when Toni’s mother will find her body, malnourished and unresponsive, in her childhood bedroom.

Those who knew Toni, including the dozens of her friends, family members, and associates interviewed for this story, will be shattered and mystified by her death. How could this vibrant young woman, beloved and admired by so many, disappear?

In piecing together, for the first time, the major events of her final months, an answer arises. And it feels like a clarion call.

Hair tied back, Toni stooped to pull weeds among the majestic redwoods. She was helping tend the grounds at Genesis, a 40-acre property north of Santa Cruz that had, in the ’70s and ’80s, housed an alternative college, the University of the Trees.

Genesis was a special place for Toni—part time-share, part think tank, part hippie commune. Member-owners joined by buying blockchain tokens, which allowed them to stop in for consciousness building, nature vibes, and more. In charge of day-to-day operations were two of her friends: crypto trader Sean Ironstag and musician/DJ Geo Star, both Burning Man regulars perpetually dressed for the playa.

Toni’s stake in Genesis was more ideological than financial. She wasn’t a member, exactly; she was more of a chronic visitor who passionately identified with its purpose. Plus, living out of a suitcase was kind of her thing, says Ironstag. He’d met Toni in the primordial bitcoin sphere years earlier, when they bonded over a seething distrust of financial institutions. Ironstag, in fact, was a convicted felon, having served time for forgery. (“I found a way to really fuck the digital banking system,” he says.) Toni didn’t judge. At various gatherings, the two friends stayed up late, deep in conversation.

During this holiday stopover, though, things at Genesis had started to lose their luster. Toni learned her cherished sanctuary was in trouble: A third cofounder, who controlled the property, wanted the others out. Normally, Toni carried herself with an almost maternal confidence that made you believe good would always prevail. But this news seemed to activate a kind of protective rage. “She was really pissed,” says Ironstag, from where he and Star sit poolside at the Palm Springs Ace Hotel years later.

Jaw set, Toni assured her friends this vital collective would not dissolve on her watch and vowed to give the cofounder “a harsh talking-to,” Ironstag remembers.

That meeting with the cofounder tested the limits of Toni’s persuasive power, in rare battle mode against someone else’s business interests. “[He] is now reversing his agreed upon terms and saying he would not like to engage in a peaceful dialogue,” she texted Ironstag. Within weeks, Genesis was no more.

EV MARQUEE

An ocean breeze blew gently as Toni rang in the New Year, cocktail in hand, partying alongside her illustrious host, crypto baron Brock Pierce. Toni had a “permanent invite” to pretty much any event he threw. “She was part of the inner circle of the industry,” says Pierce. “You weren’t in the business if you weren’t friends with Toni.”

Toni built loyalty by going to bat for other people’s ideas on the global stage. Thanks to her performance chops, she could crush a keynote—a gift that Pierce, a former teen movie actor, respected and leveraged. “Toni could explain a project’s mission better than the founder or CEO,” Pierce says. “She was a very good storyteller, very good at delivering the message. That skill set is rare.”

In 2018, Toni traveled the world with Pierce, hyping his new blockchain token EOS (the effort raised some $4 billion in crowdfunding before running into trouble with government regulators, one of several legal situations Pierce has faced in his career). She also publicized Pierce’s efforts to attract crypto investors to Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria devastated the U.S. commonwealth, killing nearly 3,000 people there. The hope, she said, was that Silicon Valley transplants would introduce tech initiatives aimed at “empowering Puerto Ricans with the tools to solve their own problems.”

Multiple insiders say the kind of work Toni did was rarely salaried. She likely received stipends in the form of highly volatile blockchain tokens. Allen Rowe, a mostly retired crypto investor who worked as Toni’s virtual executive assistant in 2018, says speaking fees appeared to be her main source of income. She set her base rate at around $5,000 plus travel costs but often settled for less than half of that. “I don’t think she ever felt she was paid fairly,” says Rowe, who earned the equivalent of $2,500 a month in Bitcoin and Ethereum working for Toni. (A single Bitcoin valued at $3,800 at the beginning of 2019 would be worth more than $71,900 as of April 2024.)

Pierce himself certainly never had Toni on payroll, he says. “I think of her as someone that worked tirelessly on behalf of the industry and was balling on a budget.”

Years later, as Pierce leaves a fancy dinner in San Juan, he’s still thinking about Toni. He and his fellow VIP guests pile into Teslas and head to a party in a gated community, gliding past walls graffitied with “Gringo go home.” It’s clear Pierce and the other investors he and Toni once hoped to attract haven’t delivered. What would Toni think if she could see this now?

“Some of the things she was working on still may get done,” Pierce says. “Her ideas were not wrong, just a little too early. Toni was basically a woman living in the future.”

Seemingly energized by the promise of new opportunities in the year ahead, Toni made stops at two major events. First up: Peer Summit in Utah, an invitation-only ideas festival held at an eco-conscious ski resort called Powder Mountain. There, wealthy blockchain innovators would converge to shape the industry, which Toni hoped would soon include Cultu.re.

She soaked in the resort’s communal hot tub surrounded by megamillionaires, despite the fact that she was often leery of powerful men. In past Facebook posts, she’d alluded to business meetings where prospective male investors had propositioned and even assaulted her. Never shy about denouncing the misogyny she’d encountered, she still did her best to focus on her mission. At Powder Mountain, that meant turning on the charm and riffing on her Cultu.re spiel for her audience. “Ninety percent of them could have personally financed the seed round of her start-up,” says Ryan Singer, a friend of Toni’s who was there.

They’d met in San Francisco around 2013, a duo of opposites—Singer, a soft-spoken tech nerd; Toni, a cosmic social star. Their relatively humble backgrounds united them, two millennials hustling to get by in an unaffordable city. By 2019, though, they were on different paths. Singer had held a number of leadership roles at start-ups and launched a few of his own, the latest being the blockchain company Chia Network. Unlike Toni, he had mastered the art of business combat.

Toni’s approach was more fake-it-till-you-make-it, acting the part of a moneyed insider. She told some people her father was an oil magnate. In reality, he runs a pool company. “She put a lot of effort into talking in a posh way,” Singer says. “She was very experimental with fashion—a lot of big fur coats and hats.” He describes little tells in Toni’s facade, like her unfamiliarity with country club leisure pursuits. When many Peer Summit attendees peeled off for a ski outing, Singer (who stayed behind) has no memory of Toni joining.

Toni’s talents were of the raw, innate variety. At a dressy group dinner, Toni cued up the pianist and serenaded the crowd. “Everybody was entranced,” Singer remembers. Yet not quite enough to win Cultu.re the backing she needed. Despite the advisers Toni had tapped to help sketch out the basics, her company’s business plan (like many business plans) was vague and jargony, lacking the clear pathway to profitability that investors like to see. “Entrepreneurs need to be able to go back and forth between being idealistic and being able to do negotiations,” says Singer. “Toni only ever did that first thing. I never saw her play hardball with anyone.”

And after Utah, Singer would never see Toni again.

Wherever she showed up, Toni always brought a certain level of intensity—it’s how she made soulmates out of acquaintances. “There was no small talk with her,” says tech founder Lucian Tarnowski, a friend and frequent festival buddy. “It was all big, meaty concepts: systems change, societal design. We would have far-reaching conversations outside of the bounds of time.”

When he crossed paths with her in the Swiss Alps at the World Economic Forum, though, Toni seemed consumed by anguished urgency. At an event that week, “she broke down weeping for the state of the world,” Tarnowski says. “Bone-chilling weeping, like a mother who was losing a child.”

He pulled her aside to talk. As much as he respected his friend’s “superhuman powers to feel,” this seemed like a spiritual crisis. Toni confided that she was in a dark place: “Bad energies” were following her, she said. And she still hadn’t secured funding for her start-up.

“One of the things our society gets so wrong is that we don’t have an effective way of rewarding the people who are at the front lines trying to find ways out of this giant mess we’re in,” says Tarnowski, who is descended from Polish aristocracy. “They tend to be almost martyrs. Where is the capital to fund those kinds of people?”

A deeper question Toni may have been confronting: Was capital even the answer?

EV MARQUEE

Between conferences, Toni holed up at a San Francisco share house known as the Crypto Castle, home to a motley crew of blockchain coders and entrepreneurs. Toni had lived there intermittently since 2015. Back then, the scene was more college dorm than coworking space. Cheez-Its and comically oversized bottles of champagne were among the main food groups.

The proprietor, a baby-faced blockchain mogul named Jeremy Gardner, was a trusted friend. He and Toni had met on a date in 2014, and while the romantic chemistry wasn’t there, a potent rapport was. The timing was fortuitous: A few weeks after meeting Gardner, Toni got evicted from an apartment and asked to crash on his couch.

“My house for years became a home base for her whenever things went wrong,” Gardner says. The relationship wasn’t one-sided though. Having come up through the Occupy Wall Street movement, Gardner drew energy from Toni’s fierce idealism, even as he counseled her to be more pragmatic about her own business plan. They could be real with each other. In social settings, she referred to him as her brother, which was kind of nice for an only child to hear.

Eventually, Gardner began to branch out from crypto, launching a skincare line and moving to Miami. And by spring 2019, the Crypto Castle had welcomed a new cohort of more subdued renters. Gardner was happy to have Toni squeeze in…at first, anyway. Tenants weren’t thrilled by the stranger sleeping on the couch while they were trying to get serious work done. Gardner started getting complaints. And although Toni insisted she was paying him rent in Bitcoin, the funds never materialized.

Gardner never imagined his last correspondence with Toni would be about money, that she would just pack up her things and disappear. If he had been more aware of her precarious state, he would’ve taken a softer approach. “I just assumed she would show up at my door again one day,” Gardner says. “That’s what Toni did.”

One morning, Toni opened the encrypted messaging app Telegram to an inquiry from a woman we’ll call Narin. It was a simple note: Narin, a virtual reality influencer based in Türkiye, was looking to track down a writer from Cointelegraph. Could Toni put them in touch?

Toni wasn’t acquainted with the writer, but she and Narin struck up a friendly text exchange. As women leaders in different tech spheres, they admired each other’s expertise. Near-daily messages soon gave way to phone calls. Narin caught feelings and invited Toni to visit her in Istanbul. Narin would pay for everything, she assured Toni. A change of scenery didn’t sound like a bad idea. Off Toni went.

Narin thought of Toni as “more than a friend.” The two of them had fun together in Türkiye, sightseeing and souvenir shopping. She even introduced Toni to a photographer, who styled her in a personal portrait session.

For Toni, though, the trip wasn’t only a lark. Narin says Toni attended at least one business meeting at an opulent 5-star hotel, where a potential client in the banking industry was apparently interested in hiring Toni to advise on a blockchain-related project. But Toni’s excitement about the potential job, however lucrative it may have been, seemed out of character: Why would she consider a banking project when she had always railed against big banks? Wasn’t she trying to launch a start-up that would radically redistribute wealth?

All Narin can say now is that something shifted after that meeting. Toni announced she was leaving Istanbul and heading to London. “I was crying,” Narin remembers. In texts and calls from that point forward, Toni seemed cold and rude, like a completely different person. Another friend of Toni’s who saw her in London says Toni spoke of “seeing spirits.”

She was alone and in crisis. Around 2:30 p.m. on July 6, a Nevada state trooper spotted a young woman walking north along a bleak stretch of US-395 just north of Reno. The temperature was a scorching 91 degrees. The woman, Toni, was dressed in black, trudging along in high-heeled boots. The trooper stopped and offered a ride, which Toni declined, according to police records. The trooper then ordered her to exit the highway a short distance up ahead and left her to it. Pedestrians weren’t allowed out there.

Toni had traveled hundreds of miles from California in the days prior. On July 1, she’d left a now-defunct spiritual retreat center near Tahoe, where something had gone awry. (“Due to a serious misalignment of values, I am looking for a new place to live as of TODAY!” she wrote in a Facebook post.) She then showed up at a friend’s Fourth of July party in San Francisco carrying her belongings in garbage bags, only to depart abruptly.

No one can explain how Toni ended up on that Nevada highway, where she walked for miles, at one point turning south. Another officer, responding to a dispatch call along with emergency medical responders, found her around 8:30 p.m. near the Reno-Tahoe International Airport. EMTs determined Toni’s condition was stable. She wasn’t dehydrated or suicidal (she wasn’t carrying drugs or weapons either). The trooper gave her a ticket and pointed her toward an exit just south of where they stood. If he saw her here again, he warned, she’d be subject to arrest.

An hour and a half later, he circled back. Toni was still there, this time north of where he’d last seen her, claiming she couldn’t find the exit. She was arrested, booked at the Washoe County jail on a misdemeanor charge, and then sent back out into the world.

EV MARQUEE

“I’m going to be in San Francisco—can I crash with you for a day or two?” Software engineer Austin Hyland was surprised when he got the text from Toni. They’d met at a blockchain conference in L.A. a couple of years prior, but they weren’t super close. Just business associates, he says (at one point, they’d discussed Hyland working with Cultu.re). No matter though. He invited her over. Anything for a pal in need.

Toni arrived carrying just a few items of clothing, without cash or credit cards. And while in one sense this might seem normal for Toni—she was all about non-government-backed currency, after all—she also seemed weirdly withdrawn. She didn’t want to talk about work or the state of the planet or much of anything at all. Had something happened?

Hyland, not knowing her very well, didn’t want to pry. “I kind of just did my best to make sure she was safe and comfortable,” he says. He tagged along as she roamed the city aimlessly, dressed in Hyland’s sweats and hoodies. After 10 days, she took off without disclosing her next move.

Toni did seek support for mental health at various points in her life. Norwegian therapist Alanja Forsberg first encountered Toni as a client at a 2018 retreat in Boulder, Colorado. Forsberg’s therapeutic approach is based on psychodrama, she explains, a group technique developed in the 1920s that incorporates elements of improvisational theater.

Toni was one of about 30 people at the retreat. She focused on unpacking sexual trauma in her past—experiences with perpetrators she chose not to report to authorities and sometimes declined to name even in private conversations. Among those suspected by friends was a prominent male figure in the crypto industry whom several other women, speaking on background, describe to Cosmopolitan as predatory and dangerous. “Most people don’t want to feel their deepest pain,” Forsberg says now via video call from Norway. “Toni went to the pain and she stood there; she fucking stayed in it.” She and Toni kept in touch, with Forsberg serving as an informal adviser of sorts.

But now Toni was FaceTiming Forsberg from an unknown airport, her usual fearless demeanor gone. She was in heightened distress, eyes darting around wildly. “She was saying, ‘They are coming after me. They are coming after me,’” Forsberg remembers. “I was like, ‘What the fuck is going on? Who are they? Who?’ I didn’t understand if she was scared of physical people in this world or spirits in other realms.”

The call ended without clear answers. Toni later resurfaced via text, seemingly in a calmer state. “I woke up this morning and wanted to fly to come to train with you. Would you be open to that?” she wrote. “I’ve been on a big journey in my healing work. My consciousness is growing.”

Forsberg wasn’t in a position to take on clients at the time. Her husband was sick; she was at capacity. Her eyes well up as she recounts this final exchange. Saying no to Toni would become “the sentence I’ve regretted most in my life.”

EV MARQUEE

Somehow, Toni found her way back to her Texas hometown. That in itself was noteworthy. Toni had been out of touch for years. Her father, Nick Casserly, says he and Toni had been close before she went down the blockchain rabbit hole. He admits he wasn’t supportive. In 2013, they’d fought over money and her lack of commitment to college. Once Toni left home, “she didn’t remain in much contact,” Nick says in an email. “She had many friends who were fiercely loyal to her.”

A high school friend confirms this, describing Toni as “so funny and smart and interesting, you were completely drawn to her. You could tell that she needed to be even bigger, and you’re like, You don’t need to be more. You’re already amazing.”

Ryan Lynch had a brief relationship with Toni in college and describes their connection as deeply spiritual. “I loved her with all my heart,” he says. “She was very complicated and hard to keep up with.” During their very first conversation in the University of Texas communications library, she engaged him for two hours on the topic of plant cultivation. Lynch, now a contractor, never stopped thinking or caring about Toni. In recent years, he’s become close with her mom. (Toni’s parents divorced when she was young, and her mother declined to comment for this story but did grant Lynch permission to share details of Toni’s final days.)

By the time Toni’s mother picked her up at the airport in August 2019, the only item in Toni’s possession was a phone. “She was obviously traumatized,” Nick says of his daughter’s emotional state, “a shell of her former self.” Toni didn’t want to see any doctors or leave her mom’s house. She spent her days snuggling with her mom’s dog, Boomer, strenuously avoiding her phone and other screens.

Toni left town again only once, in November 2019, for a high-profile speaking engagement at the Doha Debates in Paris. There, Toni would face off with a panel of other thought leaders on the question “Can we thrive without trust in government?” The debate should have been a slam dunk for Toni. But video of a one-on-one interview before the main event shows her on the defensive as the interviewer challenges her belief in blockchain technology as a replacement for nation-states.

“Do you vote?” the interviewer asks with a cool smile.

“I don’t engage in the current institutional political realm in any means,” Toni says. She’s pale; she looks tired.

The interviewer expresses smug surprise. “Wow, so you actively try not to participate in what arguably is your civic duty?”

Toni blinks, then responds. “I would say that my civic duty is that I take care of my neighbors when they get sick.”

Toni’s mom entered her daughter’s bedroom that morning to check on her. Toni hadn’t been well—fighting an infection of some kind, running a fever. For the entire month prior, she’d eaten almost nothing and continued to refuse medical care. Now, it was too late: Toni’s mother found her daughter in bed, dressed in plaid pajamas, unresponsive.

Nick Casserly announced Toni’s passing on Facebook soon after. Her far-flung crypto network responded with shocked confusion, swirling with conspiracy theories—that Toni had been murdered or brainwashed by a spiritual cult. Losing their beautiful, vibrant friend felt unimaginable. But the coroner’s report was definitive: Toni’s official cause of death was anorexia nervosa.

Anorexia has one of the highest mortality rates of all mental illnesses, says Allegra Broft, MD, an eating disorder specialist at NY-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City. While some people live for years with the condition, anorexia can lead to sudden death through medical complications such as cardiac arrest. Research shows that a large measure of people with eating disorders also meet the criteria for at least one other psychiatric disorder, such as depression, bipolar disorder, or PTSD. These co-occurring conditions can fuel one another, and successful treatment often requires a multidisciplinary care team. In cases when an adult declines professional support, “family members are often very helpless,” says Dr. Broft. She likens the experience to loving someone with a substance-use disorder. “There’s only so much you can do to intervene.”

Now, of course, everyone in Toni’s life wishes they had done more. The troubling signs were there. The subtle cries for help. The not-so-subtle ones too.

It was easy, maybe, to fault her decentralized lifestyle—no one was privy to the full scope of her life or inner world. “Everyone felt a tremendous amount of guilt,” says Gardner. “We can all blame ourselves a little for not being more proactive, for not reaching out to her or checking in on her.” And because she died early on in the COVID-19 pandemic, even Toni’s funeral was a shadow of what she deserved: a virtual memorial service over Zoom, where at least 20 people eulogized or made music in Toni’s memory. Lynch briefly tuned in from Texas. “I watched for a couple minutes but just couldn’t handle it,” he says. “Closed my laptop and just tried to bury it.” This proved impossible. Toni lived on in his dreams, lucid visions that startled him awake. Which was actually on-brand for Toni: “My real thesis on death is that we don’t actually die,” she mused in her public talks. “Your soul is potentially made up of every other soul that exists on Earth because every time someone touches you, they leave an imprint.”

Her own imprint is a cautionary parable, warning about the pressures we face to monetize our humanity, and a searing truth: Revolutionary hope will never fit into a neat business model with a bottom line.

Toni Lane Casserly died building a network. What she needed was community.

If you are struggling with disordered eating, consider reaching out to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa & Associated Disorders helpline at 888-375-7767.

Jessica Klein is a freelance journalist whose work on cryptocurrency, intimate partner violence, and curious subcultures has appeared in publications including the New York Times, The Atlantic, Elle, GQ, Fortune, and The Guardian. As a contributing reporter at The Fuller Project, she received the 2021 NAJA National Native Media Award for Best Coverage of Native America.

News

An enhanced consensus algorithm for blockchain

The introduction of the link and reputation evaluation concepts aims to improve the stability and security of the consensus mechanism, decrease the likelihood of malicious nodes joining the consensus, and increase the reliability of the selected consensus nodes.

The link model structure based on joint action

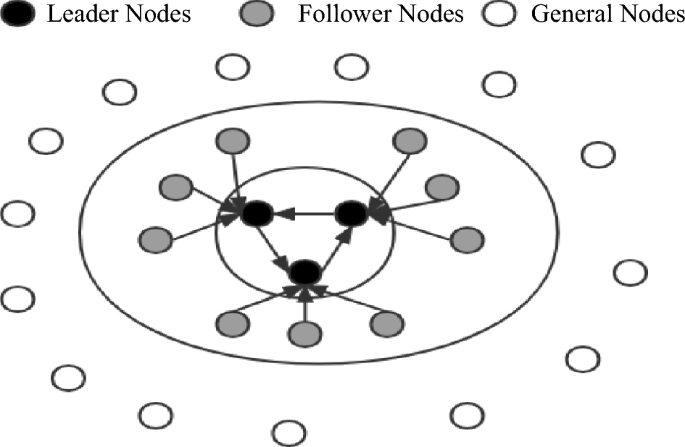

Through the LINK between nodes, all the LINK nodes engage in consistent activities during the operation of the consensus mechanism. The reputation evaluation mechanism evaluates the trustworthiness of nodes based on their historical activity status throughout the entire blockchain. The essence of LINK is to drive inactive nodes to participate in system activities through active nodes. During the stage of selecting leader nodes, nodes are selected through self-recommendation, and the reputation evaluation of candidate nodes and their LINK nodes must be qualified. The top 5 nodes of the total nodes are elected as leader nodes through voting, and the nodes in their LINK status are candidate nodes. In the event that the leader node goes down, the responsibility of the leader node is transferred to the nodes in its LINK through the view-change. The LINK connection algorithm used in this study is shown in Table 2, where LINKm is the linked group and LINKP is the percentage of linked nodes.

Table 2 LINK connection algorithm.

Node type

This paper presents a classification of nodes in a blockchain system based on their functionalities. The nodes are divided into three categories: leader nodes (LNs), follower nodes (FNs), and general nodes (Ns). The leader nodes (LNs) are responsible for producing blocks and are elected through voting by general nodes. The follower nodes (FNs) are nodes that are linked to leader nodes (LNs) through the LINK mechanism and are responsible for validating blocks. General nodes (N) have the ability to broadcast and disseminate information, participate in elections, and vote. The primary purpose of the LINK mechanism is to act in combination. When nodes are in the LINK, there is a distinction between the master and slave nodes, and there is a limit to the number of nodes in the LINK group (NP = {n1, nf1, nf2 ……,nfn}). As the largest proportion of nodes in the system, general nodes (N) have the right to vote and be elected. In contrast, leader nodes (LNs) and follower nodes (FNs) do not possess this right. This rule reduces the likelihood of a single node dominating the block. When the system needs to change its fundamental settings due to an increase in the number of nodes or transaction volume, a specific number of current leader nodes and candidate nodes need to vote for a reset. Subsequently, general nodes need to vote to confirm this. When both confirmations are successful, the new basic settings are used in the next cycle of the system process. This dual confirmation setting ensures the fairness of the blockchain to a considerable extent. It also ensures that the majority holds the ultimate decision-making power, thereby avoiding the phenomenon of a small number of nodes completely controlling the system.

After the completion of a governance cycle, the blockchain network will conduct a fresh election for the leader and follower nodes. As only general nodes possess the privilege to participate in the election process, the previous consortium of leader and follower nodes will lose their authorization. In the current cycle, they will solely retain broadcasting and receiving permissions for block information, while their corresponding incentives will also decrease. A diagram illustrating the node status can be found in Fig. 1.

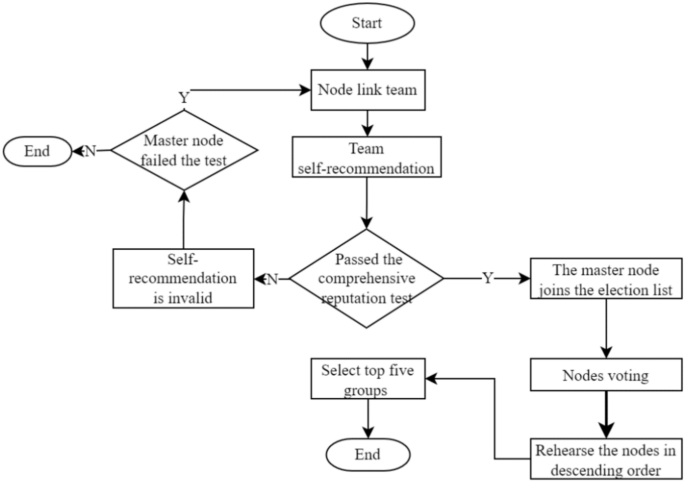

Election method

The election method adopts the node self-nomination mode. If a node wants to participate in an election, it must form a node group with one master and three slaves. One master node group and three slave node groups are inferred based on experience in this paper; these groups can balance efficiency and security and are suitable for other project collaborations. The successfully elected node joins the leader node set, and its slave nodes enter the follower node set. Considering the network situation, the maximum threshold for producing a block is set to 1 s. If the block fails to be successfully generated within the specified time, it is regarded as a disconnected state, and its reputation score is deducted. The node is skipped, and in severe cases, a view transformation is performed, switching from the master node to the slave node and inheriting its leader’s rights in the next round of block generation. Although the nodes that become leaders are high-reputation nodes, they still have the possibility of misconduct. If a node engages in misconduct, its activity will be immediately stopped, its comprehensive reputation score will be lowered, it will be disqualified from participating in the next election, and its equity will be reduced by 30%. The election process is shown in Fig. 2.

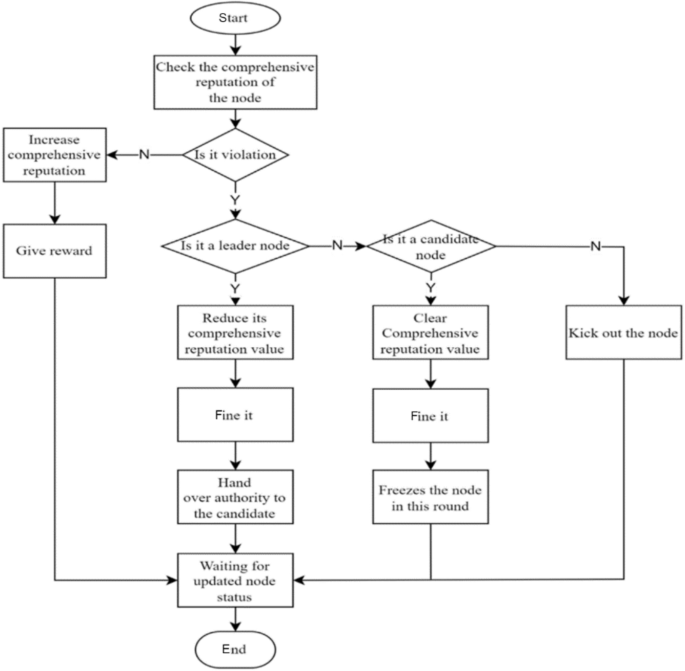

Incentives and penalties

To balance the rewards between leader nodes and ordinary nodes and prevent a large income gap, two incentive/penalty methods will be employed. First, as the number of network nodes and transaction volume increase, more active nodes with significant stakes emerge. After a prolonged period of running the blockchain, there will inevitably be significant class distinctions, and ordinary nodes will not be able to win in the election without special circumstances. To address this issue, this paper proposes that rewards be reduced for nodes with stakes exceeding a certain threshold, with the reduction rate increasing linearly until it reaches zero. Second, in the event that a leader or follower node violates the consensus process, such as by producing a block out of order or being unresponsive for an extended period, penalties will be imposed. The violation handling process is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Violation handling process.

Comprehensive reputation evaluation and election mechanism based on historical transactions

This paper reveals that the core of the DPoS consensus mechanism is the election process. If a blockchain is to run stably for a long time, it is essential to consider a reasonable election method. This paper proposes a comprehensive reputation evaluation election mechanism based on historical records. The mechanism considers the performance indicators of nodes in three dimensions: production rate, tokens, and validity. Additionally, their historical records are considered, particularly whether or not the nodes have engaged in malicious behavior. For example, nodes that have ever been malicious will receive low scores during the election process unless their overall quality is exceptionally high and they have considerable support from other nodes. Only in this case can such a node be eligible for election or become a leader node. The comprehensive reputation score is the node’s self-evaluation score, and the committee size does not affect the computational complexity.

Moreover, the comprehensive reputation evaluation proposed in this paper not only is a threshold required for node election but also converts the evaluation into corresponding votes based on the number of voters. Therefore, the election is related not only to the benefits obtained by the node but also to its comprehensive evaluation and the number of voters. If two nodes receive the same vote, the node with a higher comprehensive reputation is given priority in the ranking. For example, in an election where node A and node B each receive 1000 votes, node A’s number of stake votes is 800, its comprehensive reputation score is 50, and only four nodes vote for it. Node B’s number of stake votes is 600, its comprehensive reputation score is 80, and it receives votes from five nodes. In this situation, if only one leader node position remains, B will be selected as the leader node. Displayed in descending order of priority as comprehensive credit rating, number of voters, and stake votes, this approach aims to solve the problem of node misconduct at its root by democratizing the process and subjecting leader nodes to constraints, thereby safeguarding the fundamental interests of the vast majority of nodes.

Comprehensive reputation evaluation

This paper argues that the election process of the DPoS consensus mechanism is too simplistic, as it considers only the number of election votes that a node receives. This approach fails to comprehensively reflect the node’s actual capabilities and does not consider the voters’ election preferences. As a result, nodes with a significant stake often win and become leader nodes. To address this issue, the comprehensive reputation evaluation score is normalized considering various attributes of the nodes. The scoring results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Comprehensive reputation evaluation.

Since some of the evaluation indicators in Table 3 are continuous while others are discrete, different normalization methods need to be employed to obtain corresponding scores for different indicators. The continuous indicators include the number of transactions/people, wealth balance, network latency, network jitter, and network bandwidth, while the discrete indicators include the number of violations, the number of successful elections, and the number of votes. The value range of the indicator “number of transactions/people” is (0,1), and the value range of the other indicators is (0, + ∞). The equation for calculating the “number of transactions/people” is set as shown in Eq. (1).

$$A_{1} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {0,} \hfill & {{\text{G}} = 0} \hfill \\ {\frac{{\text{N}}}{{\text{G}}}*10,} \hfill & {{\text{G}} > 0} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$

(1)

where N represents the number of transactional nodes and G represents the number of transactions. It reflects the degree of connection between the node and other nodes. Generally, nodes that transact with many others are safer than those with a large number of transactions with only a few nodes. The limit value of each item, denoted by x, is determined based on the situation and falls within the specified range, as shown in Eq. (2). The wealth balance and network bandwidth indicators use the same function to set their respective values.

$${A}_{i}=20*\left(\frac{1}{1+{e}^{-{a}_{i}x}}-0.5\right)$$

(2)

where x indicates the value of this item and expresses the limit value.

In Eq. (3), x represents the limited value of this indicator. The lower the network latency and network jitter are, the higher the score will be.

The last indicators, which are the number of violations, the number of elections, and the number of votes, are discrete values and are assigned different scores according to their respective ranges. The scores corresponding to each count are shown in Table 4.

$$A_{3} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {10*\cos \frac{\pi }{200}x,} \hfill & {0 \le x \le 100} \hfill \\ {0,} \hfill & {x > 100} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$

(3)

Table 4 Score conversion.

The reputation evaluation mechanism proposed in this paper comprehensively considers three aspects of nodes, wealth level, node performance, and stability, to calculate their scores. Moreover, the scores obtain the present data based on historical records. Each node is set as an M × N dimensional matrix, where M represents M times the reputation evaluation score and N represents N dimensions of reputation evaluation (M < = N), as shown in Eq. (4).

$${\text{N}} = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {a_{11} } & \cdots & {a_{1n} } \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {a_{m1} } & \cdots & {a_{mn} } \\ \end{array} } \right)$$

(4)

The comprehensive reputation rating is a combined concept related to three dimensions. The rating is set after rating each aspect of the node. The weight w and the matrix l are not fixed. They are also transformed into matrix states as the position of the node in the system changes. The result of the rating is set as the output using Eq. (5).

$$\text{T}=\text{lN}{w}^{T}=\left({l}_{1}\dots {\text{l}}_{\text{m}}\right)\left(\begin{array}{ccc}{a}_{11}& \cdots & {a}_{1n}\\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {a}_{m1}& \cdots & {a}_{mn}\end{array}\right){\left({w}_{1}\dots {w}_{n}\right)}^{T}$$

(5)

Here, T represents the comprehensive reputation score, and l and w represent the correlation coefficient. Because l is a matrix of order 1*M, M is the number of times in historical records, and M < = N is set, the number of dimensions of l is uncertain. Set the term l above to add up to 1, which is l1 + l2 + …… + ln = 1; w is also a one-dimensional matrix whose dimension is N*1, and its purpose is to act as a weight; within a certain period of time, w is a fixed matrix, and w will not change until the system changes the basic settings.

Assume that a node conducts its first comprehensive reputation rating, with no previous transaction volume, violations, elections or vote. The initial wealth of the node is 10, the latency is 50 ms, the jitter is 100 ms, and the network bandwidth is 100 M. According to the equation, the node’s comprehensive reputation rating is 41.55. This score is relatively good at the beginning and gradually increases as the patient participates in system activities continuously.

Voting calculation method

To ensure the security and stability of the blockchain system, this paper combines the comprehensive reputation score with voting and randomly sorts the blocks, as shown in Eqs. (3–6).

$$Z=\sum_{i=1}^{n}{X}_{i}+nT$$

(6)

where Z represents the final election score, Xi represents the voting rights earned by the node, n is the number of nodes that vote for this node, and T is the comprehensive reputation score.

The voting process is divided into stake votes and reputation votes. The more reputation scores and voters there are, the more total votes that are obtained. In the early stages of blockchain operation, nodes have relatively few stakes, so the impact of reputation votes is greater than that of equity votes. This is aimed at selecting the most suitable node as the leader node in the early stage. As an operation progresses, the role of equity votes becomes increasingly important, and corresponding mechanisms need to be established to regulate it. The election vote algorithm used in this paper is shown in Table 5.

Table 5 Election vote counting algorithm.

This paper argues that the election process utilized by the original DPoS consensus mechanism is overly simplistic, as it relies solely on the vote count to select the node that will oversee the entire blockchain. This approach cannot ensure the security and stability of the voting process, and if a malicious node behaves improperly during an election, it can pose a significant threat to the stability and security of the system as well as the safety of other nodes’ assets. Therefore, this paper proposes a different approach to the election process of the DPoS consensus mechanism by increasing the complexity of the process. We set up a threshold and optimized the vote-counting process to enhance the security and stability of the election. The specific performance of the proposed method was verified through experiments.

The election cycle in this paper can be customized, but it requires the agreement of the blockchain committee and general nodes. The election cycle includes four steps: node self-recommendation, calculating the comprehensive reputation score, voting, and replacing the new leader. Election is conducted only among general nodes without affecting the production or verification processes of leader nodes or follower nodes. Nodes start voting for preferred nodes. If they have no preference, they can use the LINK mechanism to collaborate with other nodes and gain additional rewards.

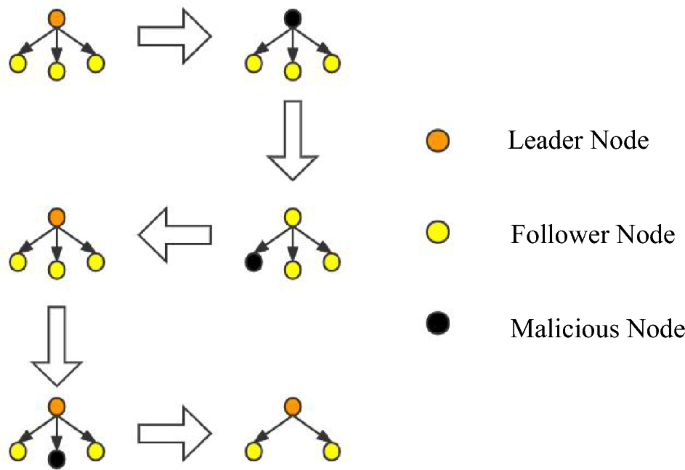

View changes

During the consensus process, conducting a large number of updates is not in line with the system’s interests, as the leader node (LN) and follower node (FN) on each node have already been established. Therefore, it is crucial to handle problematic nodes accurately when issues arise with either the LN or FN. For instance, when a node fails to perform its duties for an extended period or frequently fails to produce or verify blocks within the specified time range due to latency, the system will precisely handle them. For leader nodes, if they engage in malicious behavior such as producing blocks out of order, the behavior is recorded, and their identity as a leader node is downgraded to a follower node. The follower node inherits the leader node’s position, and the nature of their work is transformed as they swap their responsibilities of producing and verifying blocks with their original work. This type of behavior will not significantly affect the operation of the blockchain system. Instead of waiting until the end of the current committee round to punish malicious nodes, dynamic punishment is imposed on the nodes that affect the operation of the blockchain system to maintain system security. The view change operation is illustrated in Fig. 4.

In traditional PBFT, view changes are performed according to the view change protocol by changing the view number V to the next view number V + 1. During this process, nodes only receive view change messages and no other messages from other nodes. In this paper, the leader node group (LN) and follower node group (FN) are selected through an election of the LINK group. The node with LINKi[0] is added to the LN leader node group, while the other three LINK groups’ follower nodes join the FN follower node group since it is a configuration pattern of one master and three slaves. The view change in this paper requires only rearranging the node order within the LINK group to easily remove malicious nodes. Afterward, the change is broadcast to other committee nodes, and during the view transition, the LINK group does not receive block production or verification commands from the committee for stability reasons until the transition is completed.

News

The Hype Around Blockchain Mortgage Has Died Down, But This CEO Still Believes

LiquidFi Founder Ian Ferreira Sees Huge Potential in Blockchain Despite Hype around technology is dead.

“Blockchain technology has been a buzzword for a long time, and it shouldn’t be,” Ferriera said. “It should be a technology that lives in the background, but it makes everything much more efficient, much more transparent, and ultimately it saves costs for everyone. That’s the goal.”

Before founding his firm, Ferriera was a portfolio manager at a hedge fund, a job that ended up revealing “interesting intricacies” related to the mortgage industry.

Being a mortgage trader opened Ferriera’s eyes to a lot of the operational and infrastructure problems that needed to be solved in the mortgage-backed securities industry, he said. That later led to the birth of LiquidFi.

“The point of what we do is to get raw data attached to a resource [a loan] on a blockchain so that it’s provable. You reduce that trust problem because you have the data, you have the document associated with that data,” said the LiquidFi CEO.

Ferriera spoke with National Mortgage News about the value of blockchain technology, why blockchain hype has fizzled out, and why it shouldn’t.

News

New bill pushes Department of Veterans Affairs to examine how blockchain can improve its work

The Department of Veterans Affairs would have to evaluate how blockchain technology could be used to improve benefits and services offered to veterans, according to a legislative proposal introduced Tuesday.

The bill, sponsored by Rep. Nancy Mace, R-S.C., would direct the VA to “conduct a comprehensive study of the feasibility, potential benefits, and risks associated with using distributed ledger technology in various programs and services.”

Distributed ledger technology, including blockchain, is used to protect and track information by storing data across multiple computers and keeping a record of its use.

According to the text of the legislation, which Mace’s office shared exclusively with Nextgov/FCW ahead of its publication, blockchain “could significantly improve benefits allocation, insurance program management, and recordkeeping within the Department of Veterans Affairs.”

“We need to bring the federal government into the 21st century,” Mace said in a statement. “This bill will open the door to research on improving outdated systems that fail our veterans because we owe it to them to use every tool at our disposal to improve their lives.”

Within one year of the law taking effect, the Department of Veterans Affairs will be required to submit a report to the House and Senate Veterans Affairs committees detailing its findings, as well as the benefits and risks identified in using the technology.

The mandatory review is expected to include information on how the department’s use of blockchain could improve the way benefits decisions are administered, improve the management and security of veterans’ personal data, streamline the insurance claims process, and “increase transparency and accountability in service delivery.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs has been studying the potential benefits of using distributed ledger technology, with the department emission a request for information in November 2021 seeking input from contractors on how blockchain could be leveraged, in part, to streamline its supply chains and “secure data sharing between institutions.”

The VA’s National Institute of Artificial Intelligence has also valued the use of blockchain, with three of the use cases tested during the 2021 AI tech sprint focused on examining its capabilities.

Mace previously introduced a May bill that would direct Customs and Border Protection to create a public blockchain platform to store and share data collected at U.S. borders.

Lawmakers also proposed additional measures that would push the Department of Veterans Affairs to consider adopting other modernized technologies to improve veteran services.

Rep. David Valadao, R-Calif., introduced legislation in June that would have directed the department to report to lawmakers on how it plans to expand the use of “certain automation tools” to process veterans’ claims. The House of Representatives Subcommittee on Disability Assistance and Memorial Affairs gave a favorable hearing on the congressman’s bill during a Markup of July 23.

News

California DMV Uses Blockchain to Fight Auto Title Fraud

TDR’s Three Takeaways: California DMV Uses Blockchain to Fight Fraud

- California DMV uses blockchain technology to manage 42 million auto titles.

- The initiative aims to improve safety and reduce car title fraud.

- The immutable nature of blockchain ensures accurate and tamper-proof records.

The California Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) is implementing blockchain technology to manage and secure 42 million auto titles. This innovative move aims to address and reduce the persistent problem of auto title fraud, a problem that costs consumers and the industry millions of dollars each year. By moving to a blockchain-based system, the DMV is taking advantage of the technology’s key feature: immutability.

Blockchain, a decentralized ledger technology, ensures that once a car title is registered, it cannot be altered or tampered with. This creates a highly secure and transparent system, significantly reducing the risk of fraudulent activity. Every transaction and update made to a car title is permanently recorded on the blockchain, providing a complete and immutable history of the vehicle’s ownership and status.

As first reported by Reuters, the DMV’s adoption of blockchain isn’t just about preventing fraud. It’s also aimed at streamlining the auto title process, making it more efficient and intuitive. Traditional auto title processing involves a lot of paperwork and manual verification, which can be time-consuming and prone to human error. Blockchain technology automates and digitizes this process, reducing the need for physical documents and minimizing the chances of errors.

Additionally, blockchain enables faster verification and transfer of car titles. For example, when a car is sold, the transfer of ownership can be done almost instantly on the blockchain, compared to days or even weeks in the conventional system. This speed and efficiency can benefit both the DMV and the vehicle owners.

The California DMV’s move is part of a broader trend of government agencies exploring blockchain technology to improve their services. By adopting this technology, the DMV is setting a precedent for other states and industries to follow, showcasing blockchain’s potential to improve safety and efficiency in public services.

-

Ethereum12 months ago

Ethereum12 months agoEthereum Posts First Consecutive Monthly Losses Since August 2023 on New ETFs

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoCryptocurrency Regulation in Slovenia 2024

-

News12 months ago

News12 months agoNew bill pushes Department of Veterans Affairs to examine how blockchain can improve its work

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoThink You Own Your Crypto? New UK Law Would Ensure It – DL News

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoUpbit, Coinone, Bithumb Face New Fees Under South Korea’s Cryptocurrency Law

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoA Blank Slate for Cryptocurrencies: Kamala Harris’ Regulatory Opportunity

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoBahamas Passes Cryptocurrency Bill Designed to Prevent FTX, Terra Disasters

-

Regulation12 months ago

Regulation12 months agoIndia to Follow G20 Policy for Cryptocurrency Regulation: MoS Finance

-

News1 year ago

News1 year ago“Captain Tsubasa – RIVALS” launches on Oasys Blockchain

-

Ethereum1 year ago

Ethereum1 year agoComment deux frères auraient dérobé 25 millions de dollars lors d’un braquage d’Ethereum de 12 secondes • The Register

-

News12 months ago

News12 months agoEU supports 15 startups to fight online disinformation with blockchain

-

News1 year ago

News1 year agoSolana ranks the fastest blockchain in the world, surpassing Ethereum, Polygon ⋆ ZyCrypto