News

Definition, who is at risk, example and cost

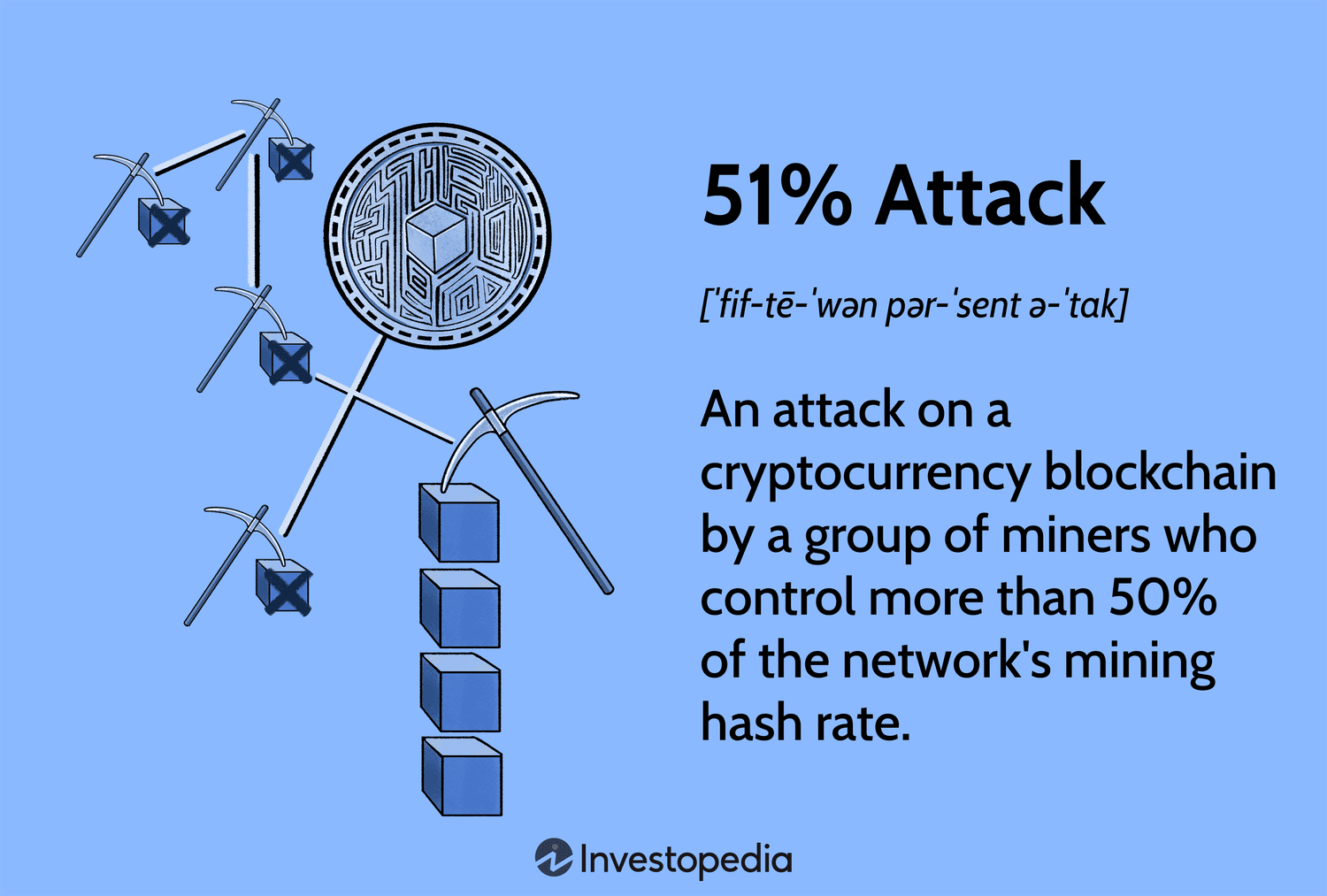

What is a 51% attack?

A 51% attack is an attack on the cryptocurrency blockchain by an entity or group that controls more than 50% of the network. If one party were to gain that much control over a network, they would have the power to alter the blockchain.

Attackers would be able to prevent new transactions from getting confirmations, allowing them to block payments between some or all users. They would also be able to cancel unconfirmed transactions completed while they were in control. Canceling transactions could allow them to double-spend coins, one of the problem mechanisms like proof of work that were created to prevent.

Key points

- Blockchains are distributed ledgers that record every transaction made on a cryptocurrency’s network.

- A 51% attack is an attack on a blockchain by an entity or group that controls more than 50% of the network.

- Attackers with majority control of the network can stop recording new blocks by preventing other miners from completing blocks.

- Changing historical blocks is impossible due to the chain of information stored in the Bitcoin blockchain.

- While a successful attack on Bitcoin or Ethereum is unlikely, smaller networks are frequent targets for 51% attacks.

Understanding a 51% attack.

A blockchain it is a distributed ledger, essentially a database, that records transactions and information about them. The blockchain network achieves majority consensus on transactions through a validation process. The blocks where the data is stored are sealed. Blocks are linked together via cryptographic techniques where information about previous blocks is recorded in each block. This makes it nearly impossible to change blocks once they have been confirmed enough times.

The 51% attack is an attack on the blockchain, in which one group controls more than 50% of the hashing (processing that solves the cryptographic puzzle) power of the network. This group then introduces an altered blockchain into the network at a very specific point on the blockchain, which is theoretically accepted by the network because the attackers would own most of it.

Changing historical blocks – transactions blocked before the attack began – would be extremely difficult even in the case of a 51% attack. The further back the transactions are, the more difficult it is to change them. It would be impossible to modify transactions before a checkpoint, where transactions become permanent in the Bitcoin blockchain.

Attacks are prohibitively expensive

A 51% attack is a very difficult and challenging task on a blockchain network with a high participation rate. In most cases, the attacker group should be able to control the necessary 51% and have created an alternative blockchain that they can insert at exactly the right time. Then, they would need to hash the core network. The cost of doing this is one of the most significant factors preventing a 51% attack.

For example, one of the most advanced application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) miners is WhatsMiner M63S. Costs over $10,000 (new) and has a hash speed of 406 terahash per second (TH/s). A single or smaller group of miners would not be able to alter and mine the Bitcoin blockchain with just a few of these machines. It would take thousands of these ASICs to outperform the Bitcoin network. Smaller networks could be overcome using these mining rigs, but the benefits of doing so would not outweigh the costs of funding the attack and setting it up.

Hashing power rental services offer attackers lower costs because they only need to rent as much hashing power as they need for the duration of the attack.

After Ethereum went proof-of-stake, a 51% attack on the Ethereum blockchain became even more costly. To conduct this attack, a user or group would need to own 51% of the ETH staked on the network. It’s possible that someone could own that much ETH, but it’s unlikely.

According to Beaconchain, more than 32.3 million ETH were staked on May 8, 2024. An entity would need to own and stake more than 16.5 million ETH (more than $49 billion as of May 8, 2024) to attempt an attack.

Once the attack begins, the consensus mechanism would likely recognize it and immediately cut off the staked ETH, costing the attacker an extraordinary amount of money. Additionally, the community can vote to restore the “honest” chain, so an attacker would lose all their ETH only to have the damage repaired.

Attack timing

In addition to the costs, a group attempting to attack the network using a 51% attack must not only control 51% of the network but also introduce the altered blockchain at a specific time. Even if they own 51% of the network’s hashing rate, they still may not be able to keep up with the block creation rate or insert their own chain before new valid blocks are created by the “honest” blockchain network.

Again, this is possible on smaller cryptocurrency networks because there is less participation and lower hash rates. Large networks make it nearly impossible to introduce an altered blockchain.

Despite the name, you don’t need to have 51% of a network’s mining power to launch an attack. However, such an attack would have a lower chance of success.

Result of a successful attack

In case of a successful attack, attackers could block other users’ transactions or cancel them and spend the same cryptocurrency again. This vulnerability, known as double expense, is the digital equivalent of a perfect counterfeit. It is also the basic cryptographic obstacle that blockchain consensus mechanisms were designed to overcome.

The 51% successful attackers can also implement a Denial-of-Service (DoS) attack, where they block other miners’ addresses for the period they control the network. This prevents “honest” miners from regaining control of the network before the dishonest chain becomes permanent.

Who is at risk of the 51% attack?

The type of mining equipment is also a factor ASIC-secure mining networks are less vulnerable than those that can be mined with GPUs; they are much faster. Cloud services like NiceHash, which considers itself a “hash power broker,” theoretically allow you to launch a 51% attack using only rented hash power, especially against smaller, GPU-only networks.

Bitcoin Gold has been a common target for attackers because it is a smaller cryptocurrency in terms of hashrate. Since June 2019, the Michigan Institute for Technology’s Digital Currency Initiative has detected, observed, or been notified of more than 40 51% attacks—also called chain reorgs or reorgs—on Bitcoin Gold, Litecoin, and other smaller cryptocurrencies.

Are the chances of a 51% Bitcoin attack growing?

On May 8, 2024, the total hashrate of the Bitcoin network was 569.29 exahash per second (EH/s). The first three mining pools for three-day hashrate they were:

- FoundryUSA, at 175.76 EH/s; 30.9% of the total hashrate of the Bitcoin network

- AntPool, at 161.77 EH/s; 28.4% of the total hashrate of the Bitcoin network

- ViaBTC, at 73.11 EH/s; 12.8% of the total network hashrate

Together, these three pools made up 72.1% of the network’s hashrate, a whopping 486.9 EH/s (486.9 million TH/s – your computer’s CPU may be able to hash at around 15 kilo hashes per second). If Foundry and ViaBTC were to collude, they could take 51% of the hashrate (248 EH/s).

Foundry and Antpool together could control 69.3% of the network. Because these pools use platforms to connect pool members and manage workloads, if managers decided to take control they could issue work orders to their pools to work on the modified chain. Pool miners would have no idea which chain they are working on as their mining rigs automatically work on whatever task they are given.

Even more concerning is that these three pools also monopolize the majority of the network’s hash rates for Bitcoin Cash, Litecoin, and Bitcoin SV.

These pools have been operating for several years without problems, but the fact remains that they already control the majority of the hashing power of mineable and profitable cryptocurrencies.

What does a 51% attack do?

A 51% attack alters the blocks that are added to the blockchain, giving attackers the ability to create or modify transactions for the period they have control.

Has a 51% attack ever happened?

YES. Several blockchains have been attacked using this method, but they had small networks, were new, or had other vulnerabilities that made it possible.

How much would a 51% attack on BTC cost?

If a large mining pool were instructed by its managers to conduct an attack, it would not cost the managers much at the time of the attack. However, he would probably lose his honest miners once they found out. For a single person or group to conduct a 51% attack, they would need more than 304 EH/s of computing power. This is a huge cost considering that the fastest miner has a hash of 406 TH/s and costs more than $10,000 per unit (about 84,000 units).

The bottom line

A 51% attack is the unlikely event in which a group acquires more than 50% of a cryptocurrency network’s hashing power. These attacks happen on smaller crypto networks, but tend to fail on larger ones like Bitcoin because they are more secure.

The comments, opinions and analyzes expressed on Investopedia are for online information purposes. Read ours warranty and exclusion of liability for more information.

News

An enhanced consensus algorithm for blockchain

The introduction of the link and reputation evaluation concepts aims to improve the stability and security of the consensus mechanism, decrease the likelihood of malicious nodes joining the consensus, and increase the reliability of the selected consensus nodes.

The link model structure based on joint action

Through the LINK between nodes, all the LINK nodes engage in consistent activities during the operation of the consensus mechanism. The reputation evaluation mechanism evaluates the trustworthiness of nodes based on their historical activity status throughout the entire blockchain. The essence of LINK is to drive inactive nodes to participate in system activities through active nodes. During the stage of selecting leader nodes, nodes are selected through self-recommendation, and the reputation evaluation of candidate nodes and their LINK nodes must be qualified. The top 5 nodes of the total nodes are elected as leader nodes through voting, and the nodes in their LINK status are candidate nodes. In the event that the leader node goes down, the responsibility of the leader node is transferred to the nodes in its LINK through the view-change. The LINK connection algorithm used in this study is shown in Table 2, where LINKm is the linked group and LINKP is the percentage of linked nodes.

Table 2 LINK connection algorithm.

Node type

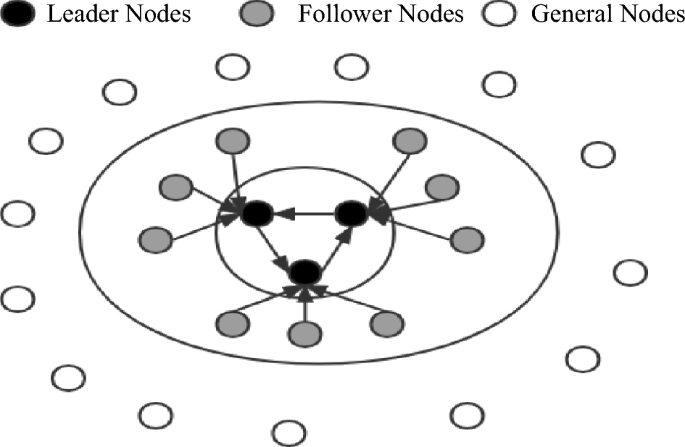

This paper presents a classification of nodes in a blockchain system based on their functionalities. The nodes are divided into three categories: leader nodes (LNs), follower nodes (FNs), and general nodes (Ns). The leader nodes (LNs) are responsible for producing blocks and are elected through voting by general nodes. The follower nodes (FNs) are nodes that are linked to leader nodes (LNs) through the LINK mechanism and are responsible for validating blocks. General nodes (N) have the ability to broadcast and disseminate information, participate in elections, and vote. The primary purpose of the LINK mechanism is to act in combination. When nodes are in the LINK, there is a distinction between the master and slave nodes, and there is a limit to the number of nodes in the LINK group (NP = {n1, nf1, nf2 ……,nfn}). As the largest proportion of nodes in the system, general nodes (N) have the right to vote and be elected. In contrast, leader nodes (LNs) and follower nodes (FNs) do not possess this right. This rule reduces the likelihood of a single node dominating the block. When the system needs to change its fundamental settings due to an increase in the number of nodes or transaction volume, a specific number of current leader nodes and candidate nodes need to vote for a reset. Subsequently, general nodes need to vote to confirm this. When both confirmations are successful, the new basic settings are used in the next cycle of the system process. This dual confirmation setting ensures the fairness of the blockchain to a considerable extent. It also ensures that the majority holds the ultimate decision-making power, thereby avoiding the phenomenon of a small number of nodes completely controlling the system.

After the completion of a governance cycle, the blockchain network will conduct a fresh election for the leader and follower nodes. As only general nodes possess the privilege to participate in the election process, the previous consortium of leader and follower nodes will lose their authorization. In the current cycle, they will solely retain broadcasting and receiving permissions for block information, while their corresponding incentives will also decrease. A diagram illustrating the node status can be found in Fig. 1.

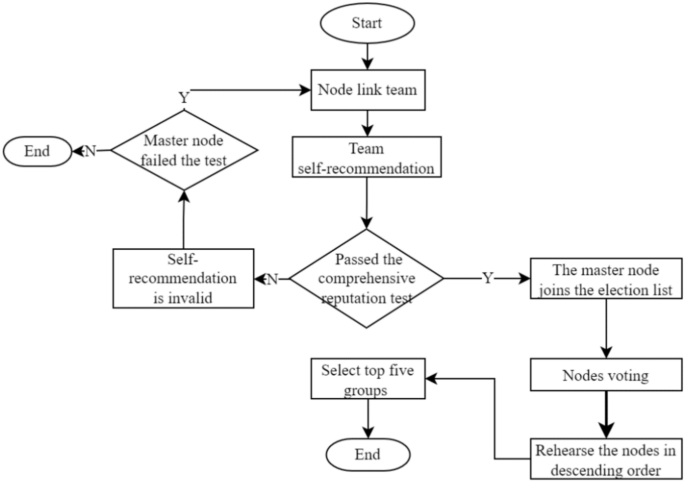

Election method

The election method adopts the node self-nomination mode. If a node wants to participate in an election, it must form a node group with one master and three slaves. One master node group and three slave node groups are inferred based on experience in this paper; these groups can balance efficiency and security and are suitable for other project collaborations. The successfully elected node joins the leader node set, and its slave nodes enter the follower node set. Considering the network situation, the maximum threshold for producing a block is set to 1 s. If the block fails to be successfully generated within the specified time, it is regarded as a disconnected state, and its reputation score is deducted. The node is skipped, and in severe cases, a view transformation is performed, switching from the master node to the slave node and inheriting its leader’s rights in the next round of block generation. Although the nodes that become leaders are high-reputation nodes, they still have the possibility of misconduct. If a node engages in misconduct, its activity will be immediately stopped, its comprehensive reputation score will be lowered, it will be disqualified from participating in the next election, and its equity will be reduced by 30%. The election process is shown in Fig. 2.

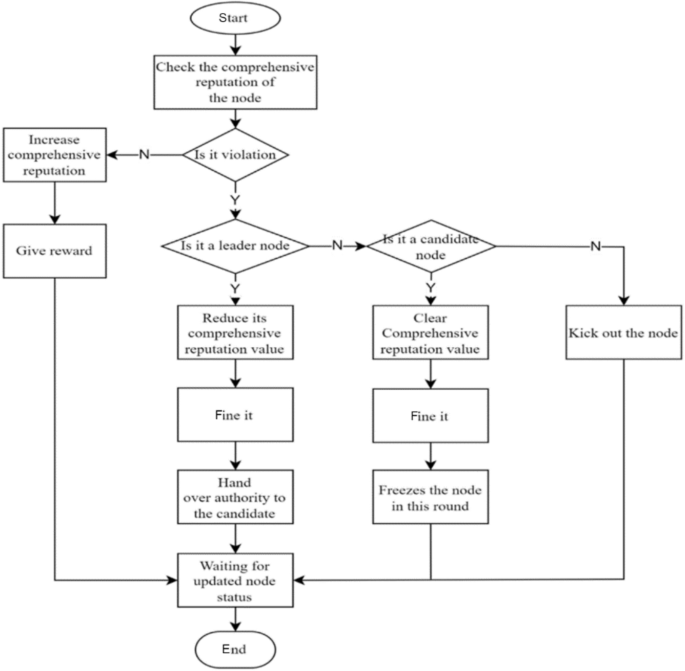

Incentives and penalties

To balance the rewards between leader nodes and ordinary nodes and prevent a large income gap, two incentive/penalty methods will be employed. First, as the number of network nodes and transaction volume increase, more active nodes with significant stakes emerge. After a prolonged period of running the blockchain, there will inevitably be significant class distinctions, and ordinary nodes will not be able to win in the election without special circumstances. To address this issue, this paper proposes that rewards be reduced for nodes with stakes exceeding a certain threshold, with the reduction rate increasing linearly until it reaches zero. Second, in the event that a leader or follower node violates the consensus process, such as by producing a block out of order or being unresponsive for an extended period, penalties will be imposed. The violation handling process is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Violation handling process.

Comprehensive reputation evaluation and election mechanism based on historical transactions

This paper reveals that the core of the DPoS consensus mechanism is the election process. If a blockchain is to run stably for a long time, it is essential to consider a reasonable election method. This paper proposes a comprehensive reputation evaluation election mechanism based on historical records. The mechanism considers the performance indicators of nodes in three dimensions: production rate, tokens, and validity. Additionally, their historical records are considered, particularly whether or not the nodes have engaged in malicious behavior. For example, nodes that have ever been malicious will receive low scores during the election process unless their overall quality is exceptionally high and they have considerable support from other nodes. Only in this case can such a node be eligible for election or become a leader node. The comprehensive reputation score is the node’s self-evaluation score, and the committee size does not affect the computational complexity.

Moreover, the comprehensive reputation evaluation proposed in this paper not only is a threshold required for node election but also converts the evaluation into corresponding votes based on the number of voters. Therefore, the election is related not only to the benefits obtained by the node but also to its comprehensive evaluation and the number of voters. If two nodes receive the same vote, the node with a higher comprehensive reputation is given priority in the ranking. For example, in an election where node A and node B each receive 1000 votes, node A’s number of stake votes is 800, its comprehensive reputation score is 50, and only four nodes vote for it. Node B’s number of stake votes is 600, its comprehensive reputation score is 80, and it receives votes from five nodes. In this situation, if only one leader node position remains, B will be selected as the leader node. Displayed in descending order of priority as comprehensive credit rating, number of voters, and stake votes, this approach aims to solve the problem of node misconduct at its root by democratizing the process and subjecting leader nodes to constraints, thereby safeguarding the fundamental interests of the vast majority of nodes.

Comprehensive reputation evaluation

This paper argues that the election process of the DPoS consensus mechanism is too simplistic, as it considers only the number of election votes that a node receives. This approach fails to comprehensively reflect the node’s actual capabilities and does not consider the voters’ election preferences. As a result, nodes with a significant stake often win and become leader nodes. To address this issue, the comprehensive reputation evaluation score is normalized considering various attributes of the nodes. The scoring results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Comprehensive reputation evaluation.

Since some of the evaluation indicators in Table 3 are continuous while others are discrete, different normalization methods need to be employed to obtain corresponding scores for different indicators. The continuous indicators include the number of transactions/people, wealth balance, network latency, network jitter, and network bandwidth, while the discrete indicators include the number of violations, the number of successful elections, and the number of votes. The value range of the indicator “number of transactions/people” is (0,1), and the value range of the other indicators is (0, + ∞). The equation for calculating the “number of transactions/people” is set as shown in Eq. (1).

$$A_{1} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {0,} \hfill & {{\text{G}} = 0} \hfill \\ {\frac{{\text{N}}}{{\text{G}}}*10,} \hfill & {{\text{G}} > 0} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$

(1)

where N represents the number of transactional nodes and G represents the number of transactions. It reflects the degree of connection between the node and other nodes. Generally, nodes that transact with many others are safer than those with a large number of transactions with only a few nodes. The limit value of each item, denoted by x, is determined based on the situation and falls within the specified range, as shown in Eq. (2). The wealth balance and network bandwidth indicators use the same function to set their respective values.

$${A}_{i}=20*\left(\frac{1}{1+{e}^{-{a}_{i}x}}-0.5\right)$$

(2)

where x indicates the value of this item and expresses the limit value.

In Eq. (3), x represents the limited value of this indicator. The lower the network latency and network jitter are, the higher the score will be.

The last indicators, which are the number of violations, the number of elections, and the number of votes, are discrete values and are assigned different scores according to their respective ranges. The scores corresponding to each count are shown in Table 4.

$$A_{3} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {10*\cos \frac{\pi }{200}x,} \hfill & {0 \le x \le 100} \hfill \\ {0,} \hfill & {x > 100} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$

(3)

Table 4 Score conversion.

The reputation evaluation mechanism proposed in this paper comprehensively considers three aspects of nodes, wealth level, node performance, and stability, to calculate their scores. Moreover, the scores obtain the present data based on historical records. Each node is set as an M × N dimensional matrix, where M represents M times the reputation evaluation score and N represents N dimensions of reputation evaluation (M < = N), as shown in Eq. (4).

$${\text{N}} = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {a_{11} } & \cdots & {a_{1n} } \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {a_{m1} } & \cdots & {a_{mn} } \\ \end{array} } \right)$$

(4)

The comprehensive reputation rating is a combined concept related to three dimensions. The rating is set after rating each aspect of the node. The weight w and the matrix l are not fixed. They are also transformed into matrix states as the position of the node in the system changes. The result of the rating is set as the output using Eq. (5).

$$\text{T}=\text{lN}{w}^{T}=\left({l}_{1}\dots {\text{l}}_{\text{m}}\right)\left(\begin{array}{ccc}{a}_{11}& \cdots & {a}_{1n}\\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {a}_{m1}& \cdots & {a}_{mn}\end{array}\right){\left({w}_{1}\dots {w}_{n}\right)}^{T}$$

(5)

Here, T represents the comprehensive reputation score, and l and w represent the correlation coefficient. Because l is a matrix of order 1*M, M is the number of times in historical records, and M < = N is set, the number of dimensions of l is uncertain. Set the term l above to add up to 1, which is l1 + l2 + …… + ln = 1; w is also a one-dimensional matrix whose dimension is N*1, and its purpose is to act as a weight; within a certain period of time, w is a fixed matrix, and w will not change until the system changes the basic settings.

Assume that a node conducts its first comprehensive reputation rating, with no previous transaction volume, violations, elections or vote. The initial wealth of the node is 10, the latency is 50 ms, the jitter is 100 ms, and the network bandwidth is 100 M. According to the equation, the node’s comprehensive reputation rating is 41.55. This score is relatively good at the beginning and gradually increases as the patient participates in system activities continuously.

Voting calculation method

To ensure the security and stability of the blockchain system, this paper combines the comprehensive reputation score with voting and randomly sorts the blocks, as shown in Eqs. (3–6).

$$Z=\sum_{i=1}^{n}{X}_{i}+nT$$

(6)

where Z represents the final election score, Xi represents the voting rights earned by the node, n is the number of nodes that vote for this node, and T is the comprehensive reputation score.

The voting process is divided into stake votes and reputation votes. The more reputation scores and voters there are, the more total votes that are obtained. In the early stages of blockchain operation, nodes have relatively few stakes, so the impact of reputation votes is greater than that of equity votes. This is aimed at selecting the most suitable node as the leader node in the early stage. As an operation progresses, the role of equity votes becomes increasingly important, and corresponding mechanisms need to be established to regulate it. The election vote algorithm used in this paper is shown in Table 5.

Table 5 Election vote counting algorithm.

This paper argues that the election process utilized by the original DPoS consensus mechanism is overly simplistic, as it relies solely on the vote count to select the node that will oversee the entire blockchain. This approach cannot ensure the security and stability of the voting process, and if a malicious node behaves improperly during an election, it can pose a significant threat to the stability and security of the system as well as the safety of other nodes’ assets. Therefore, this paper proposes a different approach to the election process of the DPoS consensus mechanism by increasing the complexity of the process. We set up a threshold and optimized the vote-counting process to enhance the security and stability of the election. The specific performance of the proposed method was verified through experiments.

The election cycle in this paper can be customized, but it requires the agreement of the blockchain committee and general nodes. The election cycle includes four steps: node self-recommendation, calculating the comprehensive reputation score, voting, and replacing the new leader. Election is conducted only among general nodes without affecting the production or verification processes of leader nodes or follower nodes. Nodes start voting for preferred nodes. If they have no preference, they can use the LINK mechanism to collaborate with other nodes and gain additional rewards.

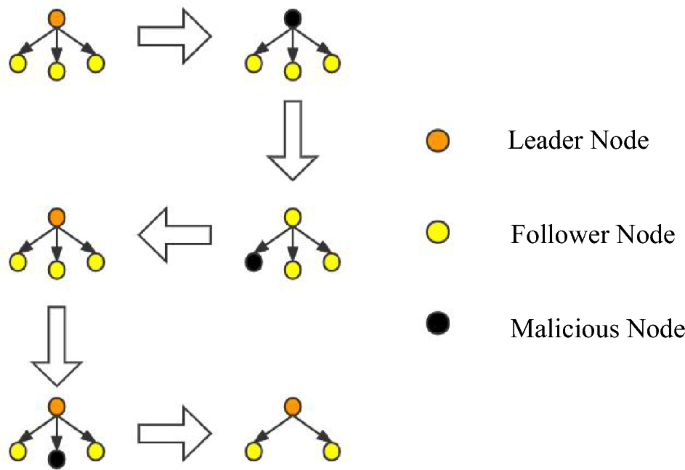

View changes

During the consensus process, conducting a large number of updates is not in line with the system’s interests, as the leader node (LN) and follower node (FN) on each node have already been established. Therefore, it is crucial to handle problematic nodes accurately when issues arise with either the LN or FN. For instance, when a node fails to perform its duties for an extended period or frequently fails to produce or verify blocks within the specified time range due to latency, the system will precisely handle them. For leader nodes, if they engage in malicious behavior such as producing blocks out of order, the behavior is recorded, and their identity as a leader node is downgraded to a follower node. The follower node inherits the leader node’s position, and the nature of their work is transformed as they swap their responsibilities of producing and verifying blocks with their original work. This type of behavior will not significantly affect the operation of the blockchain system. Instead of waiting until the end of the current committee round to punish malicious nodes, dynamic punishment is imposed on the nodes that affect the operation of the blockchain system to maintain system security. The view change operation is illustrated in Fig. 4.

In traditional PBFT, view changes are performed according to the view change protocol by changing the view number V to the next view number V + 1. During this process, nodes only receive view change messages and no other messages from other nodes. In this paper, the leader node group (LN) and follower node group (FN) are selected through an election of the LINK group. The node with LINKi[0] is added to the LN leader node group, while the other three LINK groups’ follower nodes join the FN follower node group since it is a configuration pattern of one master and three slaves. The view change in this paper requires only rearranging the node order within the LINK group to easily remove malicious nodes. Afterward, the change is broadcast to other committee nodes, and during the view transition, the LINK group does not receive block production or verification commands from the committee for stability reasons until the transition is completed.

News

The Hype Around Blockchain Mortgage Has Died Down, But This CEO Still Believes

LiquidFi Founder Ian Ferreira Sees Huge Potential in Blockchain Despite Hype around technology is dead.

“Blockchain technology has been a buzzword for a long time, and it shouldn’t be,” Ferriera said. “It should be a technology that lives in the background, but it makes everything much more efficient, much more transparent, and ultimately it saves costs for everyone. That’s the goal.”

Before founding his firm, Ferriera was a portfolio manager at a hedge fund, a job that ended up revealing “interesting intricacies” related to the mortgage industry.

Being a mortgage trader opened Ferriera’s eyes to a lot of the operational and infrastructure problems that needed to be solved in the mortgage-backed securities industry, he said. That later led to the birth of LiquidFi.

“The point of what we do is to get raw data attached to a resource [a loan] on a blockchain so that it’s provable. You reduce that trust problem because you have the data, you have the document associated with that data,” said the LiquidFi CEO.

Ferriera spoke with National Mortgage News about the value of blockchain technology, why blockchain hype has fizzled out, and why it shouldn’t.

News

New bill pushes Department of Veterans Affairs to examine how blockchain can improve its work

The Department of Veterans Affairs would have to evaluate how blockchain technology could be used to improve benefits and services offered to veterans, according to a legislative proposal introduced Tuesday.

The bill, sponsored by Rep. Nancy Mace, R-S.C., would direct the VA to “conduct a comprehensive study of the feasibility, potential benefits, and risks associated with using distributed ledger technology in various programs and services.”

Distributed ledger technology, including blockchain, is used to protect and track information by storing data across multiple computers and keeping a record of its use.

According to the text of the legislation, which Mace’s office shared exclusively with Nextgov/FCW ahead of its publication, blockchain “could significantly improve benefits allocation, insurance program management, and recordkeeping within the Department of Veterans Affairs.”

“We need to bring the federal government into the 21st century,” Mace said in a statement. “This bill will open the door to research on improving outdated systems that fail our veterans because we owe it to them to use every tool at our disposal to improve their lives.”

Within one year of the law taking effect, the Department of Veterans Affairs will be required to submit a report to the House and Senate Veterans Affairs committees detailing its findings, as well as the benefits and risks identified in using the technology.

The mandatory review is expected to include information on how the department’s use of blockchain could improve the way benefits decisions are administered, improve the management and security of veterans’ personal data, streamline the insurance claims process, and “increase transparency and accountability in service delivery.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs has been studying the potential benefits of using distributed ledger technology, with the department emission a request for information in November 2021 seeking input from contractors on how blockchain could be leveraged, in part, to streamline its supply chains and “secure data sharing between institutions.”

The VA’s National Institute of Artificial Intelligence has also valued the use of blockchain, with three of the use cases tested during the 2021 AI tech sprint focused on examining its capabilities.

Mace previously introduced a May bill that would direct Customs and Border Protection to create a public blockchain platform to store and share data collected at U.S. borders.

Lawmakers also proposed additional measures that would push the Department of Veterans Affairs to consider adopting other modernized technologies to improve veteran services.

Rep. David Valadao, R-Calif., introduced legislation in June that would have directed the department to report to lawmakers on how it plans to expand the use of “certain automation tools” to process veterans’ claims. The House of Representatives Subcommittee on Disability Assistance and Memorial Affairs gave a favorable hearing on the congressman’s bill during a Markup of July 23.

News

California DMV Uses Blockchain to Fight Auto Title Fraud

TDR’s Three Takeaways: California DMV Uses Blockchain to Fight Fraud

- California DMV uses blockchain technology to manage 42 million auto titles.

- The initiative aims to improve safety and reduce car title fraud.

- The immutable nature of blockchain ensures accurate and tamper-proof records.

The California Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) is implementing blockchain technology to manage and secure 42 million auto titles. This innovative move aims to address and reduce the persistent problem of auto title fraud, a problem that costs consumers and the industry millions of dollars each year. By moving to a blockchain-based system, the DMV is taking advantage of the technology’s key feature: immutability.

Blockchain, a decentralized ledger technology, ensures that once a car title is registered, it cannot be altered or tampered with. This creates a highly secure and transparent system, significantly reducing the risk of fraudulent activity. Every transaction and update made to a car title is permanently recorded on the blockchain, providing a complete and immutable history of the vehicle’s ownership and status.

As first reported by Reuters, the DMV’s adoption of blockchain isn’t just about preventing fraud. It’s also aimed at streamlining the auto title process, making it more efficient and intuitive. Traditional auto title processing involves a lot of paperwork and manual verification, which can be time-consuming and prone to human error. Blockchain technology automates and digitizes this process, reducing the need for physical documents and minimizing the chances of errors.

Additionally, blockchain enables faster verification and transfer of car titles. For example, when a car is sold, the transfer of ownership can be done almost instantly on the blockchain, compared to days or even weeks in the conventional system. This speed and efficiency can benefit both the DMV and the vehicle owners.

The California DMV’s move is part of a broader trend of government agencies exploring blockchain technology to improve their services. By adopting this technology, the DMV is setting a precedent for other states and industries to follow, showcasing blockchain’s potential to improve safety and efficiency in public services.

-

Ethereum11 months ago

Ethereum11 months agoEthereum Posts First Consecutive Monthly Losses Since August 2023 on New ETFs

-

Regulation11 months ago

Regulation11 months agoCryptocurrency Regulation in Slovenia 2024

-

News11 months ago

News11 months agoNew bill pushes Department of Veterans Affairs to examine how blockchain can improve its work

-

Regulation11 months ago

Regulation11 months agoThink You Own Your Crypto? New UK Law Would Ensure It – DL News

-

Regulation11 months ago

Regulation11 months agoA Blank Slate for Cryptocurrencies: Kamala Harris’ Regulatory Opportunity

-

Regulation11 months ago

Regulation11 months agoUpbit, Coinone, Bithumb Face New Fees Under South Korea’s Cryptocurrency Law

-

Regulation11 months ago

Regulation11 months agoBahamas Passes Cryptocurrency Bill Designed to Prevent FTX, Terra Disasters

-

Regulation11 months ago

Regulation11 months agoIndia to Follow G20 Policy for Cryptocurrency Regulation: MoS Finance

-

Ethereum1 year ago

Ethereum1 year agoComment deux frères auraient dérobé 25 millions de dollars lors d’un braquage d’Ethereum de 12 secondes • The Register

-

Videos1 year ago

Videos1 year agoNexus Chain – Ethereum L2 with the GREATEST Potential?

-

News11 months ago

News11 months agoEU supports 15 startups to fight online disinformation with blockchain

-

News1 year ago

News1 year agoSolana ranks the fastest blockchain in the world, surpassing Ethereum, Polygon ⋆ ZyCrypto